|

Financial Imperatives

for DRE A significant amount of the rural population in India still lacks access to reliable forms of electricity. With the constraints faced in resource availability and in delivery mechanisms, there is a tremendous opportunity for electricity supply using renewable resources. In this context, decentralised renewable energy (DRE) solutions for a country like India are economically and environmentally smart options. Evidence shows that DRE based micro-grids offer cheaper options compared to diesel generators and kerosene. The policy architecture in India around DRE projects however has not been able to trigger confidence amongst service providers, technology suppliers and investors to venture beyond demonstration projects.

Policies related to rural electrification and promotion of renewable energy favour large producers of electricity and grid-connected users through a range of incentives for supply of green power to the grid. In the case of off-grid models, there are several bottlenecks or roadblocks in the schemes and policies which act as barriers to its implementation leading to lack of innovative service delivery models. A vicious circle is thus initiated, discouraging interest of both private and public entities in renewable energy based decentralised power projects. A major factor for this is lack of low cost financing options. Access to credit facilities is crucial for facilitating access to clean energy technologies, especially for relatively capital-intensive DRE systems. The high upfront cost of DRE technology options makes them unreachable for the common rural consumers unless backed by some support and access to financing. The high up-front costs classify the sector as high-risk leading to unavailability of viable financing options for off-grid DRE projects, despite them being promoted under government schemes (Prayas, 2012b). The existing fiscal measures as well as financing mechanisms do not encourage small-scale entrepreneurs to set up such plants. In fact, no robust financing mechanism exists for supporting off-grid renewable energy projects (NRDC 2012), which take care of start-up capital as well as aid in overcoming running costs in the initial years of functioning (CSTEP, 2011). For instance, currently Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) has very limited provisions for support of biomass based micro-grids and in cases where such support is provided the same is limited to either capital subsidy or interest subsidy. Owing to the consumptive nature of energy, cumbersome procedures involved in accessing formal credit and reluctance of formal banking system to provide credit acts as a huge barrier for setting up systems to meet rural energy needs. Other barriers include: • Technology obsolescence• Enormous paper work and costs associated with identifying and obtaining access to finance for small and medium scale RE projects• Limited understanding of RE in financial institutions• Lack of familiarity and awareness of technologies, particularly for those that have recently achieved commercialisation.Further, especially in the context of DRE mini-grids projects, the RE project developers would be small, independent and newly established, lacking the institutional track record and the financial strength to secure non-recourse project funding. To improve the existing situation, there is a need for action particularly with respect to financing of DRE based micro-grids. A few recommendations regarding the same have been given below: 1. Introduction of financial instruments to reduce risk and increase profitability of private entrepreneurs: a. Risk Capital: There is a need to look into the possibility of complete funding for risk capital to protect the interests of private sector investment in DRE. b. Project Insurance: The MNRE / other ministries can create an insurance scheme around operational disruption to safeguard interests for the Energy Supply Companies (ESCO) as well as the financiers. c. Bridge Financing: More sources of equity for promoters to bridge the gap between what they can contribute and the target capitalisation structure is required. The same can be availed through government subsidies worth approximately 15% of the project cost or other innovative financial instruments. d. Partial Risk Guarantee Fund: Having a partial risk guarantee fund would aid in initiating greater financial sector participation, by acting as a risk mitigation option. The fund would act as a buffer in case one of the stakeholders defaults on payments 2. Financing schemes around Feed-in Tariff (FiT) can be a cost-effective mechanism and achieve two diverse needs: one of providing sustainable and affordable electricity to local users in remote locations in developing countries and the other to make renewable energy projects attractive to policy-makers (World Future Council, 2009). Although capital costs of renewable energy projects are much higher than a conventional genset, FiTs help to offset the large capital costs associated with RET. Feed-in tariffs are intended to increase the adoption of renewable energy technologies, encourage the development of the RE industry, and provide significant economic development benefits. India at present has attempted to provide for FiT rates for grid-connected projects but no mechanism exists for off-grid projects. Moreover, information asymmetry in the Indian situation makes it difficult to determine the most justifiable rate, which would be further alleviated in the context of off-grid models. Moreover, the rates need to be high enough to encourage investments and low enough to avoid over subsidising. However, the success of financing through FiTs to encourage investment in off-grid projects has been seen especially in the European context, and thus it has the potential of being a viable option for increasing investment opportunities in India as well. 3. Priority Sector Status to

Small DRE projects to encourage financial assistance:

At present, off-grid projects in the eyes of the

government as well as financing institutions lack significance. The need

for establishing its significance stems from the very nature of

renewable energy systems (renewable sources are varied and depend on

geography) and their capacity (plants are

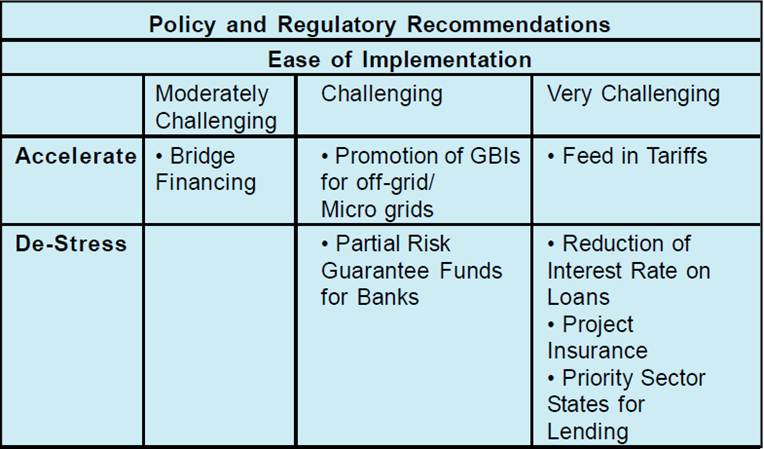

The table ‘Policy and Regulatory Recommendations’ collates the recommendations mentioned above and prioritises them on the basis of ease of implementation. It forms an indicative base for initiating work, which will lead to promotion and increased private investments for DRE based micro-grids in India. There is a conclusive need to accelerate private sector participation in the sector, which is mostly through better financing mechanisms. The steps taken for acceleration need to be coupled with steps to de-stress the current policy and regulatory environment. Currently, private investments in DRE based micro-grids is encouraged in policies on paper, but their operationalisation and provisions make it a high risk and cumbersome initiative. New business models must be set up, and the policy and regulatory scenario around them should be made conducive for the replication and scale-up of DRE based micro-grids. The potential of these models is slowly being realised, but the changing policy environment must be tracked relentlessly to steer it in the favour of such models. q Vrinda Chopra, Shivani Mathur References: 1. CEEW & NRDC (2012) Laying the Foundation for a Bright Future: Assessing Progress under phase 1 of India’s National Solar Mission. Council of Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW); National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Shakti Foundation 2. CSTEP (2011) Universal Energy Access by 2030: Technology, Economics, Policy. Note for GSP, Version 2.0. Prepared for Minister of Environment and Forests, India. Centre for Study of Science, Technology and Policy

|

smaller in size). For

financing such projects, a major step would be provisioning dedicated

credit facilities especially for DRE projects, by including the RE

sector under the priority sectors for lending. Currently, the priority

sectors include agriculture, small-scale industries and other

activities/borrowers. This step would aid in increasing the availability

of credit to this sector and lead to larger participation by commercial

banks, encouraging investments from small and medium scale

entrepreneurs. A beginning in this

direction has been made in the recent Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

notification wherein off-grid renewable energy projects for households

being promoted by individuals have been considered.

smaller in size). For

financing such projects, a major step would be provisioning dedicated

credit facilities especially for DRE projects, by including the RE

sector under the priority sectors for lending. Currently, the priority

sectors include agriculture, small-scale industries and other

activities/borrowers. This step would aid in increasing the availability

of credit to this sector and lead to larger participation by commercial

banks, encouraging investments from small and medium scale

entrepreneurs. A beginning in this

direction has been made in the recent Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

notification wherein off-grid renewable energy projects for households

being promoted by individuals have been considered.