Measuring Access to

Electricity -

Turn the Framework Around

Maximise Access and Installed Capacity

T

he Sustainable Development Goal number 7 of achieving universal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy by 2030 was adopted in 2015 by the UN General Assembly1. The fact that the objective is linked to increased access to electricity and not to the increased amount of electricity generated sends a clear message that it is the share of households with access which is assumed to be the true driver of human development. The objective of universal access to sustainable energy is based on the experience that such access is one of the key drivers of poverty alleviation and human development through its enabling role for education, communication and productive use.Apart from universal access, the SDG also mentions reliable and modern energy. This is an important qualifier to have for end mile consumers connected to the central grid, as often the electricity that reaches these consumers comes at random hours during the day and that too of low voltage. This impacts the luminosity for lighting and the potential use for income generating livelihoods.

Ideally, in most public policies and strategies, electrification should be developed with an objective of maximising the expected development impact per unit of money invested, not only the capacity installed. The success of an electrification objective should be based on the impact, not the input. In order to maximise the development impact, focus going forward should be on maximising access to reliable electricity services for the budget available, rather than maximising added power generation capacity.

Monetary Value of Electricity

The problem in this context is that the standard analysis frameworks applied by governments, institutions and donors for developing electrification plans and policies fail to properly capture the development value of access to electricity. The standard ‘Power Merit Order’ prioritises projects based on cost per watt installed or per kilowatt hour (kWh) generated. However, research indicates that the value of a kWh in a development perspective is dependent on its use. The development value is likely higher for one kWh used to provide high quality evening lighting to 60 off-grid households, relative to running one machine wash or 45 minutes of air conditioning for one grid connected household with the same kWh.

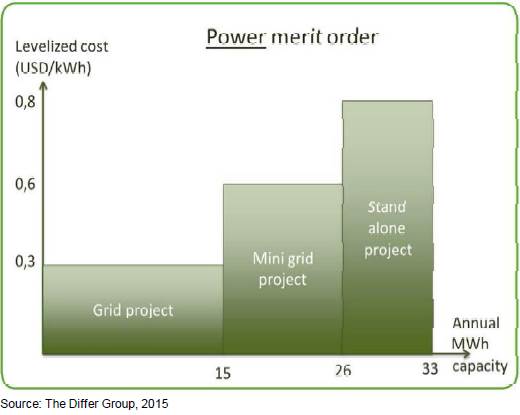

The same way, India assesses the Levelised Unit Cost of Electricity (LUCE) of different electrification efforts based on the traditional power generation i.e. Lowest cost per installed capacity (Wp or KWh). This Power Merit Order typically shows that a grid project has the lowest cost per KWh generated.

This is reflected in our country’s large scale electrification efforts as well, where extending the existing grid and adding thermal power plants are seen as the best way forward to provide electricity to the 75 million unelectrified

2 rural households.Development Value of Electricity

With energy efficiency measures in basic household

appliances, 1 Kwh/week can give you 4 lightbulbs, mobile charging and a TV.

A fan run on DC electricity may require slightly more than 1 KwH. With this

low energy consumption required for basic services, the traditional power

generation order fails to reflect the very high development impact of these

services provided within 1 Kwh. With access to lighting, entire generations

can be educated. It can be seen that these first few Kwhs providing access

to basic services like lighting have the highest development impact per Kwh.

The fact that lighting for a household can now be provided with 80-90% less

Kwhs though the use of LED bulbs instead of incandescent light bulbs does

not reduce the development impact from providing light, even if the power

used is now very small.

Along the same vein, the UN Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL) Global Tracking Framework defines six different tiers of access (Electricity service levels) ranging from no access (Tier 0 or 1) to 24x7 access to run any high power appliance (Tier 5)

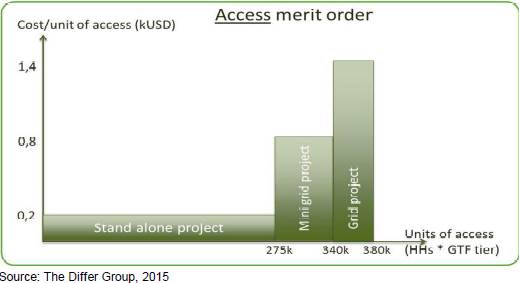

3. An electrification intervention which targets Tier 1 or 2 would impact a larger number of households at a much larger scale of impact. The number of households then becomes the unit of measurement.This changed unit, when put into a framework, reflects the true value of each Kwh. As an addition to the Power Merit Order, it is time for an ‘Access Merit Order’. Instead of measuring cost per ‘unit of power’ (i.e. per Watt or kWh), this new framework measures cost per ‘unit of access’. If the unit power i.e. Kwh is replaced with ‘units of access’, a different picture will emerge for electrification efforts. For example, if the tiers of access are multiplied by the number of households provided access, each project represents a number of access units. The total budget allotted for electrification efforts divided by units of access gives the cost per unit of access.

For un-electrified areas, you could experience that the ‘Access Merit Order’ reverses the relative attractiveness of the projects compared with the ‘Power Merit Order’

4.

All the households that receive access to electricity will be able to use this electricity to reduce their spending on kerosene, dry batteries, candles and/or diesel generators. Hence, there is a modest, but significant ability to pay for the electricity received in order to secure a robust electricity service that later can be maintained and scaled.

Allowing for this perspective and taking into account a model of community co-financing, projects will be able to provide access to an even higher number of households over time, making the payback time for a stand-alone solution 40 months. Disallowing the hidden subsidies, a grid project comparatively has a payback time per connection of 550 months.

Financing and Scaling the Development Goal of Access

The year 2014 was a successful year for energy access companies, securing at least $64 million in investments

5. The investment one gets can be either debt financing or equity. Debt financing signals achievements of past success as opposed to equity which is riskier. Though difficult to obtain, debt investment is essential for attracting commercial banks, which are vital to truly scale the energy access sector.Scaling of the energy access sector is what is truly required for effectively implementing a goal which says universal access to all. Behind the SDG Goal 7 lies an expectation that in order to achieve it the share of population gaining access increases and not doubling of global energy installed capacity and generation.

In order to get the highest possible development impact per unit of money invested in electrification, the Access Merit Order could be actively used alongside the Power Merit Order when electrification strategies are devised and revised going forward. Only then can access be the key driver of development and poverty alleviation. q

Rowena Mathew

rmathew@devalt.org

Endnotes

1 United Nations. 2015. Sustainable Development Goals.2 Census of India. 2011.

3 SE4All. 2015. Global Tracking Framework – Key Findings.

4 The Differ Group. 2015. The Access Merit Order.

5 Lipton, Chad. 2015. "Microgrids Key to Bringing a Billion Out of the Dark". National Geographic.