| Efficiency in a Complex World Ashok Khosla akhosla@devalt.org

The pursuit of efficiency currently dominates the thinking of most of our leaders today. It has, in fact, become the supreme or over-riding objective of most societies. But, there is evidence that this single-minded pursuit of efficiency is also driving our civilisation to destroy many of the things on which we depend for our existence? What are the trade-offs and sacrifices we are prepared to make to achieve higher levels of efficiency? And, who gets the benefits of greater efficiency – and who pays the costs? Is efficiency to be synonymous with profitability or is its meaning to be broadened to mean the care and protection of our one and only (and rather fragile) planet? And, when it comes down to brass tacks, what is efficiency anyway? Is it a clearly defined concept? Would everyone agree to its definition? Is there any way to define it so that it encompasses the other concerns rather than being in a contest with them for our attention? The many sides of efficiency Any student who enters a course in the physical sciences soon comes across the concept of efficiency. One of the first things we learned in high school physics (given the state of education today, one may now have to wait until college) is that efficiency is a measure of the success achieved relative to the effort expended. Quantitatively, it is simply the ratio of output to the input. The fraction of what goes in as raw materials or energy that ends up as useful product. Engineers, being more mathematically inclined, often define it as the ratio of two ratios: actual mechanical advantage over ideal mechanical advantage – but it amounts to the same thing since the denominators cancel out. And chemists are even more sophisticated. They know how to define the efficiency of a process at several different levels, depending on which of the nature’s limits is operating in the process. These limits are described by the three laws of thermodynamics. So, a process may be very efficient under the First Law of Thermodynamics, but may not be at all efficient under the Second Law. Cooking with electricity is a prime example of this: a cooking range is extremely efficient for transferring heat to the cooking pot but making electricity in the first place is a highly inefficient process. Thus, this is not a good way to use electricity which has many other possible uses that are far more valuable, such as running machines, separating chemical substances or even lighting. For those of you who are not familiar with the three laws of thermodynamics, you may well have encountered their equivalents outside the classroom: they are, in fact, no different from the three well-known laws of the Casino:

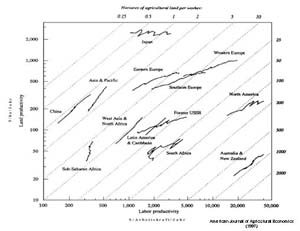

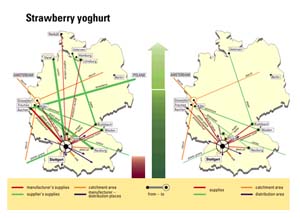

The most important point to remember about efficiency is that it is not an abstract, absolute thing. Efficiency is measured in terms of a given input, and for the same product or output, it can be, and often is, different for different inputs: land, labour, resources, knowledge, capital. The chart below, taken from a 1997 issue of the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, shows that the agricultural systems adopted by the Japanese are as different from those in North America or Australia as day is from night. One maximises the productivity of land (which in Japan is scarce and every farmer has an acre or so) and the other maximises the productivity of labour (which in America and Australia is very expensive and every farm worker has a thousand times more than in Japan). Which, is "better"? Efficiency in the real world Economics has sometimes been called the "dismal science". Dismal yes, "Allocative" is not to be confused with "distributive". The term allocative is used by economists primarily to refer to the sharing of raw materials and inputs (including the various factors of production, land, natural resources, labour, knowledge and capital) to the productive processes of the economy. Its meaning subsumes the concept of efficiency. The latter term, distributive, on the other hand, refers to the sharing of the output among different segments of the population, at the consumption end, and has elements of fairness and "distributive justice" associated with it. These two seemingly identical concepts are, in the mind of the economist, actually completely distinct – though even they often confuse them and get them mixed up. Adam Smith’s focus on specialisation and David Ricardo’s analysis of comparative advantage were simply to identify tools to achieve greater efficiency – in production. Markets may be no good for equity or social justice or the environment but because they do tend to promote some degree of efficiency in the allocation of resources to different uses, they are the favourite mechanism of the economics profession. In this respect, incidentally, Karl Marx was no different from the classical economists: he simply wanted to assert the primacy of labour over capital in deciding who gets the benefits of the production system and therefore, in the longer run, has the purchasing power as a consumer. Pareto introduced some rigour into this relationship by defining the most efficient economic option as the one for which no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off. Kaldor and Hicks broadened the scope of such optimality by including those who would be willing to accept compensation for not being better off those who do become better off, thus establishing a net benefit for society as a whole. But John Maynard Keynes understood that markets can fail and studied Another type of efficiency measure proposed by the Harvard economist Harvey Leibenstein concerns itself with the fraction of ideal production a firm actually puts out. He found a wide variety of limiting factors, including the motivation of entrepreneurs, the work ethics of the employees and defined a new concept, X-efficiency to describe this type of inefficiency, which he attributed to lack of competitive forces. The central goal of neo-classical economics and modern economic theory, competitiveness, is actually just another term for efficiency. Competition and efficiency go together. For businesspersons, efficiency and competitiveness is all about cutting costs and maximising profits. The most profitable company is the most efficient. And vice versa. In a perfect market, this means that the resources, processes and innovation in the firm are being managed in a manner that cannot be improved in terms of profitability. Such profitability guarantees that the firm has been able to manage its ability to supply things in sufficient quantity to meet the demand (a good part of which it may have created and manipulated through clever advertising and marketing methods). But, it has little to do with efficiency in real terms – in terms of meeting people’s felt needs with the resources available on this planet. Efficiency with less than full cost accounting The trouble is that neither the economist nor the business person wishes to acknowledge the real costs of their inputs and outputs. It is the prices they face in the market that determines their decisions — not the full costs as ecologists would call them or the actual costs as any ordinary housewife would easily recognise them. A story that illustrates the enormous gap between how engineers, economists and business people see efficiency and how scientists, ecologists and environmentalists see it is exemplified by the carton of strawberry yoghurt, which as many of you know, is the favourite breakfast food in Germany. A colleague at the Wuppertal Institute in Germany followed the movements of this product starting from the dairy where the milk originated to its destination in a small carton on the breakfast table. The journey ended up taking her all over the continent of Europe. The carton of strawberry yogurt actually arrives on that breakfast table after its ingredients have made a journey of some 4,500 kilometres. In addition, the suppliers’ inputs had already travelled 3,500 kilometres. That is a movement of some 8,000 kilometres, in a country that is not short of milk and strawberries of its own. Clearly, this must make eminent sense from the point of view of the business. (Otherwise, why would they do it?). This may well be the least cost and therefore the most "efficient" way to deliver a breakfast food to a home in Germany — given the prices that are actually paid for the raw materials, fuel and infrastructure use. But for nature, it is a disaster. And the reason, of course, is that the prices paid for energy, transport and other services are hugely subsidised. The environment actually pays the bulk of the real cost (by absorbing pollution, acid rain, deforestation, floods and other societal costs). Society pays some in accepting noise, congestion, accidents and loss of various amenities. And, governments pay the rest (through subventions that help to underprice and therefore promote over-utilization of the resources). The autobahns, like our roads; the petrol, like our fuels, the fertilisers and pesticides for the strawberries, like our own chemical inputs are all sold at prices that do not take account of the devastation, depletion and pollution of our natural resources, nor of the exploitative wages paid for labour. The map at the top depicts the travel of ingredients (Strawberry Yoghurt) from the Wuppertal Institute’s research.

One may well say that this story reflects the grossly distorted pricing structure of transportation and energy in Europe. What does it have to do with India? Well, quite a lot, really. For one thing, our prices are far more distorted than those in Europe and the costs of ecosystem services are even less well integrated into them. Secondly, we have the same mindset problem, only worse since we have not had the time to observe the impacts of such a market. One example of such a mindset concerns the serious advice given by an eminent marketing expert who had formerly been a senior executive of a major multinational FMCG to Development Alternatives for marketing the high efficiency chulhas (woodstoves) it designs and sells for use by village housewives. The chulhas are designed to be manufactured locally, close to the point of sale to minimise costs and to create jobs and local capacity at the same time. His serious suggestion was that the only successful strategy to scale up the market would be to make the product in a centralised facility and deliver it by truck all over the country, "just like soap". He said that the business of business is to make money and not to worry about issues such as environmental protection, employment generation or the national good. Our discussions with other captains of industry suggest that – with a few notable exceptions – this is not an isolated view, which means that the more "efficient" they are the more destruction of our natural systems we can expect. They also forget that as soon as the subsidies for energy, transport and other services that make possible long range marketing are withdrawn, they will be left standing high and dry. Factor 4 today Factor 4 represents the improvements that must be made in the efficiency with which we use our material resources – i.e., in material productivity. This means that with current technologies and minor changes in our production and distribution systems, a doubling of wealth can be achieved while halving the quantity of resources that are used. Professor Ernst von Weizsaecker in Germany and his collaborators, have collected numerous examples of how this is possible and have written a wonderful book on how it is already being done in many different contexts. You may well say that all these resource conservation issues are relevant for the rich countries but are just conversation for the poor ones like us. We need to create much more wealth before we can start worrying about saving resources. Unfortunately, there is a huge fallacy in that argument. Certainly, we need to improve the lives of a huge number of our fellow citizens, each by a huge amount. As fast as possible. But this does not mean that we can be cavalier about the resources nature has given us to make this possible. The fact that India’s footprint is already twice the size of the country and twice the global average means that it is even more important for us than for others to find better, more resource conserving ways to satisfy people’s needs. This requires much higher resource productivity than is available through the technologies and production systems that we are buying or copying from the richer countries. Factor 10 does not mean slowing down the "development" of our economy but rather to choose a different path to make secure, safe and fulfilling lives for all using far less material and energy resources. But let me give you a more specific example from a systems optimisation I undertook some 30 years ago. You will recall that because of the Six Day War in the Middle East, and the coming into its own of OPEC, the price of petrol suddenly shot up at the end of 1973. I was then working as the director of the Division of Environment in the Ministry of Science and Technology. It occurred to me one night that the bus system of Delhi, which then had some 2,500 buses on the city’s routes and carried, if I recall correctly, some 1.5 million passengers per day, could be better designed and should be able to carry a far greater number of passengers if some basic changes were made in the routes and frequencies of the services. The trouble, as I saw it, was that the Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) had routes that had grown in a haphazard way over the years and wound and wove their way from one end of the city through all kinds of twists and turns to the other end. The implicit objective of the routing was to provide as many direct origin-destination connections so that passengers could get to where they were going without having to change buses. Under such circumstances, it was understandable that they measured the efficiency of the system basically in terms of the number of passenger-miles carried (and of course fares collected). But this did not give DTC’s management any particular insight into what potential or latency there existed for efficiency improvements. Their routes and services responded to the origin-destination data, which in turn were collected in the framework of the existing system. So, the question of making any fundamental changes in the system never surfaced. I worked with DTC to develop a whole new approach to running its buses. We set up a hub and spoke system, with a crucial ring road service (refer the diagram below). The key was to maintain the highest possible speeds and the maximum possible frequencies – the ring road service, in both clockwise and counter clockwise directions was running as much as one bus every two or three minutes. In this system, it was essential to take long-distance commuters on express, non-stop buses, instead of tying up their time and that of the bus (which was the scarce resource) stopping every few hundred meters letting off and picking up passengers. The local routes would then provide them last mile connections from the main, fast, non-stop routes. The system was designed to ensure rapid changeovers and give commuters many choices, encouraging them to take a bus going in the right direction rather than to exactly the right place. We don’t have the time to go into the details but I can tell you that within three months, without adding a single new bus, we were carrying more than double the number of passengers. In other words, we had released a hidden capacity in the buses of more than 100%. This capacity was in the potential category, because we simply arranged things so as to get the passengers out of their seats and out of the buses in less than half the time. This meant that the bus could make twice as many trips per day, essentially doubling its capacity. In terms of the earlier paradigm, the capacity utilisation (another facet of efficiency) was pretty high – in fact more than 100 per cent, as was evidenced by the number of passengers hanging on to the bus from all sides. In terms of the new routing-scheduling system, it was less than 50 per cent. This is the meaning of potential efficiency. The then General Manager of DTC, Mr SK Sharma, with whom I am still privileged to work closely, and I went on to explore even higher realms of efficiency – what I have earlier called latent efficiency – by a wide variety of debottlenecking exercises, such as introducing dozens of bus depots to provide the much higher level of maintenance needed for buses that were now doing twice the mileage, bus interchange nodes and bays for bus stops, one-way streets, improved bus designs for quicker passenger movement and fare structures to encourage passengers to take quicker routes, even if they covered longer distances and other measures. These involved some, though not very large investments and made it possible for DTC to carry even larger number of passenger-miles. Possibilities for systemic efficiency improvements will come from improved communication systems (already happening), courier services, location of residential and work facilities, and progressively higher level interventions. q Ashok Khosla [First Part of the Fifth Dr PR Srivinivasan Memorial Lecture | |||||||||

particularly from the point of view of the poor and the marginalised; but science? – a lot of people might consider that a bit of an exaggeration. As a subject of study, economics – like any other subject – is neither good nor bad. Like all others, it is a legitimate and important field of investigation. The problem arises from the choice and scope of specific topics that its professionals focus on — the methods they use, the value judgements they make and the praxis they influence with their theories. In this respect, I think the subjects contemporary economists deal primarily with, could be better described as the (almost ruthless, and not always salutary) "pursuit of efficiency at the expense of all else". Economists like markets because they are "efficient". Any first year economics textbook will tell you that "Allocative efficiency is the market condition whereby resources are allocated in a way that maximises the net benefit attained through their use." At this point, at which supply meets demand, the market is ticking over with maximum efficiency.

particularly from the point of view of the poor and the marginalised; but science? – a lot of people might consider that a bit of an exaggeration. As a subject of study, economics – like any other subject – is neither good nor bad. Like all others, it is a legitimate and important field of investigation. The problem arises from the choice and scope of specific topics that its professionals focus on — the methods they use, the value judgements they make and the praxis they influence with their theories. In this respect, I think the subjects contemporary economists deal primarily with, could be better described as the (almost ruthless, and not always salutary) "pursuit of efficiency at the expense of all else". Economists like markets because they are "efficient". Any first year economics textbook will tell you that "Allocative efficiency is the market condition whereby resources are allocated in a way that maximises the net benefit attained through their use." At this point, at which supply meets demand, the market is ticking over with maximum efficiency.  the conditions under which the economy settles down to less than complete use of its resources (labour, capital, natural resources, etc.) because of inadequate aggregate demand. Such conditions prevent the economy from working at full efficiency and can be responsible for large scale unemployment co-existing with less than the full output it is capable of.

the conditions under which the economy settles down to less than complete use of its resources (labour, capital, natural resources, etc.) because of inadequate aggregate demand. Such conditions prevent the economy from working at full efficiency and can be responsible for large scale unemployment co-existing with less than the full output it is capable of.