| Agenda 2007: Every Village a Knowledge Centre V. Ranjit Khosla rkhosla@tarahaat.com

As a result of a series of studies and meetings starting in May 2004, a large group of organizations have joined together to form a National Alliance with the purpose of making every village a knowledge centre by 2007, the 60th anniversary of India’s independence. Convened by the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF) in Chennai, it received strong inputs and endorsement from a wide variety of players ranging from the NASSCOM Foundation to the Ministry of Information Technology, from ITC and Azim Premji Foundation to Microsoft, from the IITs to the IIITs, and from Development Alternatives and TARAhaat to OneWorld South Asia and the National Foundation of India. The 41 founding members of the Alliance, with the active involvement of Dr MS Swaminathan, represent much of the effort now being made to bring the benefits of modern ICT into the lives of the people of our country. To take the movement forward, the Alliance has set up 7 Task Forces to define the various issues and elements that will be needed to meet its ambitious goals. Development Alternatives was invited to convene the Task Force on Organisation and Management, to design the most effective institutional framework for this purpose. The draft paper prepared for discussion by the Alliance is presented below, in the hope that readers of this Newsletter will help refine it. T he villages of India vary widely in their geography, economy, demographics and other attributes. Some are no more than small hamlets, while others can easily be mistaken for a small town. Some are located right next to a national highway; many others are in isolated, remote and inaccessible places. The economy of the Indian village is largely characterized by poor infrastructure; many have no all-weather roads or reliable electricity or telephone connections. A typical village offers very few local job opportunities, especially for its youth, and has virtually no local industry. Facilities for education, social services and entertainment are even more limited. Studies by NCAER and others have shown, however, that there is considerable purchasing power in rural India, though much of it goes into consumption spending since there are few opportunities to invest in off-farm productive capacity. demographics and other attributes. Some are no more than small hamlets, while others can easily be mistaken for a small town. Some are located right next to a national highway; many others are in isolated, remote and inaccessible places. The economy of the Indian village is largely characterized by poor infrastructure; many have no all-weather roads or reliable electricity or telephone connections. A typical village offers very few local job opportunities, especially for its youth, and has virtually no local industry. Facilities for education, social services and entertainment are even more limited. Studies by NCAER and others have shown, however, that there is considerable purchasing power in rural India, though much of it goes into consumption spending since there are few opportunities to invest in off-farm productive capacity. Any structure and strategy to reach deep into every village throughout the nation must be designed to be able to address this variety and remoteness. For such structures and strategies to be successful, they must be responsive to local needs and aspirations, and therefore highly decentralised. For such structures and strategies to be sustainable, they must in the long run be financially viable, and therefore be designed so as to generate revenue streams that are sufficient to recover the costs of the services they provide. A key missing link that prevents the village from rapidly developing its human and physical resources, and therefore its economy, is access to knowledge. Not just the formal knowledge normally acquired in schools and colleges but, more particularly, the knowledge its citizens need to create secure livelihoods and lives for themselves and thus contribute to building up the resources and economy of their community. Much of this information exists somewhere, in some form or other, and at some level of applicability and relevance. But to be of value to the villager, it must be accessed, adapted, interpreted, and communicated in a form that he or she can comprehend and put to practical use – at a price that is reasonable. An example is the setting up of a local industry; say a small cold storage plant. Such an industry can be of enormous value to every farmer in the locality, vastly increasing their potential earnings and reducing their risks for every crop. A villager with entrepreneurial skills wishing to set up such a plant would need large amounts of information … on the business opportunity (a simple business plan), on the kinds of equipment needed and where, how and for how much to procure these, on where to obtain financing, including accessing grants and loans from government schemes, on how to set it up and operate it, how to get assured power and how to market its services … all of which could be obtained through a well designed information system. But even if he or she is armed with all this information, the entrepreneur will still need specialist advice on how actually to set up and operate the plant to make it profitable and successful. Another example is the need of a farmer to buy a tractor. A well designed knowledge service should be able to help the client get all the information needed in one package, preferably at one (electronic) window. This package should provide, at a glance, the various types of tractors available and their respective advantages and shortcomings, the vendors for each make, the financing sources and their terms, the government subsidies available, the ancillaries available and the additional opportunities for generating income when the tractor is not needed for agricultural operations. Such information packages and services are not commonly available in rural India. The latest advances in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) offer highly efficient and cost-effective methods for providing them on a nationwide basis. Moreover, if such services are properly designed to take advantage of the economies possible from decentralised delivery systems and multiple revenue streams, they could be provided on a sustainable, commercial footing by private entrepreneurs. This paper attempts to identify the design criteria for setting up an organizational framework and a system of management that can effectively bring the ICT revolution into "every" Indian village within the 3 year time frame envisaged. Such an organizational framework will have to be multilevel, decentralised and, in its essence, quick-footed and non-bureaucratic. It will have to adopt the best attributes of the public sector (e.g., attention to universal service provision and scaling up), the private sector (business-like strategies and sense of urgency), academia (innovation, experimentation and rigour of analysis) and civil society (social objectives and direct participation in people’s processes). It will, in fact, have to build active collaboration among the sectors (so-called "public-private" partnerships) to take advantage of the strengths of each and the synergies possible, which happen to be particularly strong in the field of ICT. And it will have to deal with all the main functional requirements of making "every village a knowledge centre":

All of these requirements are critically important. Since steps are being taken to improve connectivity and infrastructure, however, developing content and creating the network of shared access points (IT Kendras) are certainly the ones that now need the most attention on the ground level, while supporting infrastructure for capacity building and access to finance require focus at the institutional level. Special attention needs also to be given to the provision of reliable electricity at affordable prices, which will probably require much greater emphasis on renewable energy sources. To enable every village to become a knowledge centre on a sustainable basis, several basic pre-requisites have to be in place: At the village level:

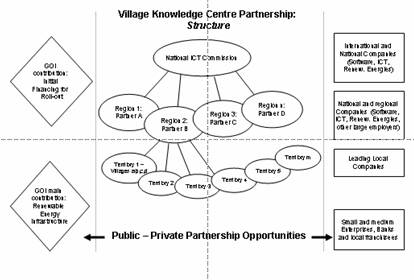

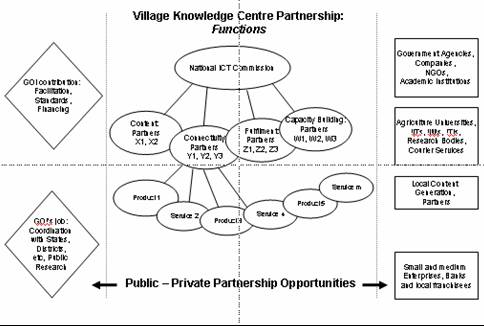

The most effective model available in India for achieving the goal of "Every Village a Knowledge Centre" is the "mission-oriented" independent commission such as the Atomic Energy Commission and the Space Commission. Suitably modified, an independent "National ICT Commission" with a limited time mandate, of say five years, could take us a long way towards this goal. The broad structure and functions of such a Commission are shown schematically in the two diagrams above, which also identify the kinds of partnerships and networking arrangements it will have to adopt. Initial establishment of such a commission will need a collaborative initiative on the part of Government, Private Sector, the Research Community and NGOs. In large measure, the work of the MSSRF and others to put together a National Alliance to this end is already in place to serve this purpose. Monitoring and Evaluation of the work of the ICT Commission will be much simpler than is required for the usual project based approaches followed in the past. The metrics for tracking the progress are, in the initial stages, quite simple (numbers of users, numbers of villages, and numbers of mini-enterprises set up as a result of the presence of ICT Kendras). As the progress towards the goal of reaching every village builds up, other metrics will need to be introduced, including measures of cost-effectiveness and impact. Many of these methodologies are being developed currently by Development Alternatives in a new approach called Monitoring, Evaluation And Learning (MEAL), which can be shared with the ICT Commission or its equivalent when it is set up. q

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||