|

The Wealth in Organic Waste

Where

do People Draw a Line Between Resource and Waste? The European Union defines waste as ‘any substance or object which the holder discards or intends or is required to discard’ (European Parliament & Council, 2008), a definition which has remained unchanged since 1975. This definition requires us to ask a different set of questions - What are the reasons for discarding a substance? What aspects make a substance valuable enough to reduce the intention of discarding? Does the price of a substance make it easier to discard than to reuse? Too often, a large sum of the price is paid by the environment. In India, waste management is seen through the lens of impact on the environment under the Environmental Protection Act of 1986, which governs the disposal, management and regulations for different waste streams. Logic demands that whoever has a larger impact on the environment, pays a bigger price, acts responsibly and adopts sustainable practices. But how does this work on an individual or household level? According to the amended Solid Waste Management Rules in 2016, it is mandatory to segregate waste in order to channelise the waste into wealth by recovery, reuse and recycle. Institutions, market generators, hotels, restaurants, event organisers have been made responsible for segregating and sorting the waste and along with urban local bodies ensuring that the food waste collected will eventually be used for bio-methanation/ composting.

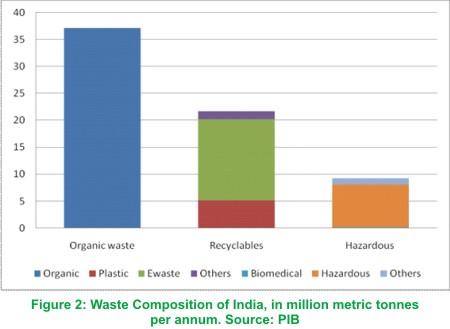

Creation of Wealth from Organic Waste Unlike many waste streams, organic waste comes into the system with pre-existing value in the form of nutrients. The typical household waste consists of 60% organic matter. Even out of the total waste produced in India, nearly 50% is organic (Figure 2), which includes organic municipal waste and agricultural waste. While the volumes of recyclables and biomedical/ hazardous waste are growing each year as India becomes more urbanised (McKinsey Global Institute 2010), the potential of organic waste to reintroduce nutrients to the system is an aspect that cannot be ignored in the drive towards sustainable development and a circular economy. The value that nutrient cycling can add to the environment has not yet been looked into at a policy level by the Indian government.

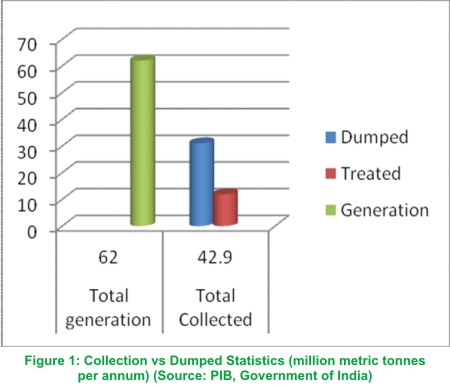

Overall, less than 60% of the waste is

collected from households and only 15% of urban India’s waste is

processed (Figure 1) (PIB 2016), which leaves the remaining waste

improperly disposed, posing a health hazard and a potential contaminant

to land and water. Uncontrolled decomposition of organic waste in

dumpsites leads to emission of potent Burning garbage is classified as the third biggest cause of greenhouse emissions in India - apart from the impact on human health; the effect on land, water and food pollution is a matter of grave concern. Burning releases CO, NO, SO2 and carcinogenic hydrocarbons, apart from particulate matter into the air, resulting in India releasing 6% of methane emissions only from garbage, compared to a 3% global average (Planning Commission 2014). Government of India’s 2016 Solid Waste Management rules mandate that waste with 1500 Kcal/kg and above should be used for co-incineration in cement and power plants, but the high moisture and organic content of the municipal wastes renders options such as RDF (Refuse-Derived Fuel) and WTE (Waste to Energy) plants ineffective, due to the low calorific value of organic waste (Annepu, 2012). Incineration of food waste consisting high moisture content results in the release of dioxins which may further lead to several environmental problems (Kunwar Paritosh, 2017). Also, leachate from the rotting garbage in waste dumping sites contains heavy metals and toxic liquids; which end up either absorbed into the soil or flowing into water bodies. The entire food chain can be affected when this contaminated water is utilised for agriculture or for human and animal consumption. The Swachh Bharat Mission had committed to ensuring that all organic waste produced in Indian cities is processed into making compost by October 2019, but currently, not even 5 per cent of organic waste generated by cities is converted into compost (Centre for Science and Environment CSE). India produces close to 1.5 lakh tonnes of solid waste every day and its biodegradable fraction (that can be converted into nutrient rich compost and returned to the soil) ranges between 30 per cent and 70 per cent for various Indian cities. As there is clear difficulty in ensuring that once the organic waste gets segregated at source, it gets processed into compost through a centralised treatment system, decentralised waste treatment systems are the most sustainable and efficient way of managing organic waste. Apart from the efficient resource use in carrying out this process, it also brings about a social responsibility within individuals, communities and organisations to take care of the waste they generate and add the lost nutrients back into the soil. This means there is a huge potential for compositing and assessing sustainable methods of processing wet waste. Need for Land By 2047, it is expected that 1,400 sq.km. of landfill area would be required for dumping India’s increasing volumes of municipal solid waste. This space is roughly equal to the combined area of three out of top five most populous cities in India: Hyderabad, Mumbai and Chennai (Annepu, 2012). There is a need to identify the points of interventions and pain points within the system in all cities first, then to identify how and where organic waste streams can be converted into wealth. As waste-to-energy is not a viable option in Indian conditions, other solutions which take into consideration the nutrient contents of the waste need to be found. As a success story, Indore has managed to introduce and implement household segregation of waste and door-to-door collection despite multiple challenges and a lack of initial political acceptance. These issues were overcome by demonstration of the system in 2 wards and then expanded through the city. This methodology helped gather public participation and build trust towards the municipality. This was an example of a multipronged approach to the problem of urban waste, with many companies distributing household waste segregation dustbins and provided vehicles to the waste collectors under CSR projects. Primarily, waste avoidance and secondly, waste disaggregation has to be considered as the main drivers for sustainable development of Indian cities. In this context, our country’s objective must be to reconcile the scarcity of our natural resources with the huge quantities of waste produced by our cities, while our individual contribution should be to segregate our waste at source to make these solutions a little easier to implement. To acknowledge Government of India’s waste management guidelines, we only need to ask ourselves, what value does this waste hold? Where do you draw the line between a resource and waste? ■

Apurva Singh References

|

greenhouse gases.

greenhouse gases.