|

Integrating Gender

Perspective into The impacts of climate change are most dramatically felt through changes in water - changes that will severely affect humans, societies and the environment. And whenever clean water is scarce, the livelihoods of the poor and women are often the first to suffer the consequences. “Women play a central part in the provision, management and safeguarding of water.” Dublin Principle 3, International Conference on Water and the Environment Development Issues for the Twenty-first Century, Dublin, 1992

The UN Sustainable Development Goals have

three dedicated goals for Gender Equality (SDG 5), Clean Water and

Sanitation (SDG 6) and Climate Action (SDG 13). Water management

connects all these goals. Identifying inter linkages between these goals

will facilitate more effective implementation of the goals. Gender

equality and gender responsive activities are also recognised elements

in the Paris Agreement. One of the main keys to fulfilling the goals set

out in the Paris Agreement will be wise water management. Gender Disparities: Increasing Vulnerability of Women to Climatic Risks Women, especially in the rural context, due to historical discrimination and biases in both the formal and informal labour markets as well as cultural and social practices, have less assets, income and savings to deal with the loss and damages from extreme weather events. As gendered work and family responsibilities make poor women the main cleaners and caregivers, poor women are the ones most affected by water and climate change issues (Moraes and Perkins, 2009). As a part of the project titled, ‘Enhancing climate resilience of women, adolescents and children in Rajasthan’, a detailed Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) study in three districts (Baran, Jalore and Udaipur) in Rajasthan with 1500 women provided evidence which highlights the vulnerabilities of women.

Policy Recommendations There is an interdependency between Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 - ‘achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’ and SDG 6 - ‘ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all’. Experiences around the world have shown that moving in this direction calls for mainstreaming gender. At the same time, women themselves are already strong advocates for their own concerns, which have become a central part of the water agenda at many levels (Yoon, 1991). Recommendation 1: Promoting Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) The principles of IWRM are needed to be stressed and advocated if sustainable adaptation strategies to climate change are to be realised. Mechanisms must be put in place to cut across sectors and link programmes and strategies dealing with water and climate issues in concrete ways. The implementation along with radical thinking would help in water management. Recommendation 2: Capacity Building of Women Training on various aspects of the PRIs regarding community assets, financial management, education, understanding of bureaucratic structures, government schemes for the rural poor, public distribution system etc. should be provided to the women members and concerned local officials. It is crucial to develop women’s leadership and decision-making skills through training, mentoring and skill building. Women’s productivity in using water for agriculture and small business also needs to be improved through training, market linkages and access to information. Recommendation 3: Enhanced Participation in Decision Making Stakeholder involvement must be the backbone of all the processes, particularly in the case of women, since their knowledge of livelihood planning and of agriculture and the environment often go unrecognised and untapped. It should be ensured that women are adequately represented in all decision-making processes, at all levels. All stakeholders within the planning process and while designing any adaptation strategy need to ensure that empowerment of women is a priority and all programmes must be gender-sensitive. Women’s participation in Water User Committees (WUCs) has been limited. They could be empowered through greater participation. Recommendation 4: Mainstreaming Gender in the Existing and Upcoming Policies and Frameworks to Ensure Sustainability It is essential to develop gender-inclusive policies and enact legislations to accelerate women’s advancement. In addition, engaging and promoting women’s unique adaptive capacities would allow decision makers to pursue policies that build resilience in communities while also promoting gender equality. Some suggested actions: - Mobilising resources to improve access to safe water and sanitation - Promoting access to sanitation Conclusion Gender-sensitive approaches to water resources management are desirable for achieving efficiency, social equity and gender-equality goals. The UN Commission on Sustainable Development has very aptly affirmed that ‘water has a woman’s face’. It is through these women’s hands that households, communities and entire health and economies are sustained. However, this heavy burden often impedes women’s education, income earning opportunities and social, cultural and political involvement. Engaging women is fundamentally important for durable climate change adaptation, particularly during climatic stresses. Adopting gender-sensitive approaches therefore means rethinking water development in a number of ways. Greater community engagement and capacity building will be key to furthering gender equality in water management. ■

Deepa Chaudhary References

|

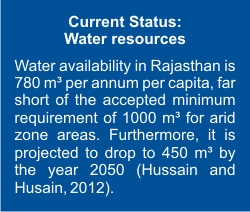

community. The onus of bringing water

from far off distances (2-5 kms), its management and storage is on

women. On an average, women in these areas walk for more than 14,000 km

a year just to fetch water. This excessive work has reduced their time

for leisure and has also adversely impacted their health.

community. The onus of bringing water

from far off distances (2-5 kms), its management and storage is on

women. On an average, women in these areas walk for more than 14,000 km

a year just to fetch water. This excessive work has reduced their time

for leisure and has also adversely impacted their health.