|

Mainstreaming Inclusive Entrepreneurship

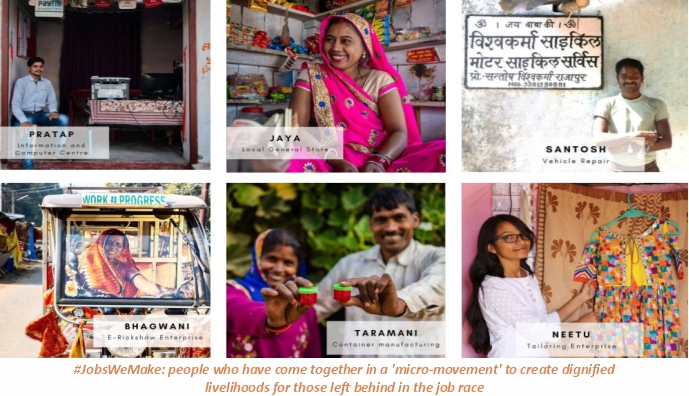

Can entrepreneurship be inclusive? Perhaps not, from the point of view of an individual entrepreneur. In most societies, it is paradigmatic to assume that there is an element of competitiveness embedded in the idea of entrepreneurship on account of which one entrepreneur must profit at the cost of another. Creating jobs is something an entrepreneur does. Nurturing other entrepreneurs, most likely not. It falls therefore, to actors at a higher “system level” to help people set up businesses, especially in those contexts where aspiring entrepreneurs do not have the means to do so themselves. When seen collectively, particularly through a social and economic well-being lens by agents of change in civil society, the idea of inclusive entrepreneurship does not seem so obscure. In fact, from a sustainable development perspective, it becomes an imperative particularly in economies such as that of India. More than ever before, we are confronted with the consequences of wealth being concentrated in the top one fifth of society, reducing the number of job creating entities outside the public sector to an increasingly narrow set of businesses and large corporations. In parallel, an induced proclivity of people towards mass production and consumption has swollen the ranks of job seekers and those engaged in lowly paid, mind numbing occupations. Is this an irreversible trend? To think of it as an inevitable outcome of development that prioritizes growth measured in GDP terms and other such macro-economic indicators puts people and our planet in grave danger. On the environmental front, we may have already crossed the point of no return and are now faced with the prospect of having to cope with permanently altered ecological systems. Socially and economically, there may still be a window of opportunity. Are there ways in which the exclusion of hundreds of millions of people from realising the “shareholder value” from entrepreneurial ventures can be arrested before we experience catastrophic failure? The answer lies, in large measure, in acknowledging the potential of those people whom most governments, large corporations and financial institutions fail to take cognizance of and most commonly refer to as entrepreneurs in the “informal” or “unorganized” sector - those women and men who use their wits, a meagre resource base and incredibly small amounts of capital to build lives for themselves and create jobs for those within their communities. An estimated 80 to 100 million “Entrepreneurs of Hope”, exist in every village, town and city of the country of India. They constitute 80% of the working population and yet are an unclassified segment of our economy suffering from a systemic apartheid in the policy landscape. They are caught in no man’s land – not poor enough to be eligible for handouts and not well-off or large enough to attract the attention of banks or intermediaries at the tail end of supply chains so assiduously cultivated by business houses. In a country that remains inherently entrepreneurial and where grassroots entrepreneurship has been widely acknowledged as a beacon of hope, very little has been done to tap entrepreneurial ambition. There are systemic gaps that prevent millions to self-actualize their economic aspirations and turn communities in both rural, small town and peri-urban India into thriving, sustainable centres of value creation. There is evidence to suggest that the threshold of entrepreneurship can be crossed by those who would have otherwise not done so. The co-creation of local ecosystems – which teammates at Development Alternatives prefer to call “micro-movements” – can lead to dramatic outcomes in the form of unleashing entrepreneurship and enhancing access to resources needed to set up and expand businesses. Pioneers such as Asha Devi, Tara Mani, Mamta, Veer Singh and Komal, who can be followed by looking up #JobsWeMake, have transformed their lives and created sustainable livelihoods for thousands of people in some of the most underdeveloped districts of Uttar Pradesh. Nationally, how big is the challenge? Even if we base projections on conservative estimates and allow for an accelerated transition in employment to formal, urban jobs, over one-third of the 12 million people entering India’s workforce each year will need to be employed in the rural non-farm sector. At an average of 3 jobs per grassroots enterprise, this alone will necessitate the setting up of over 1 million new businesses every year. We believe that a movement towards inclusive entrepreneurship will, simply put, bring more people into the ambit of entrepreneurship and create more jobs in such enterprises. And thus, we see inclusive entrepreneurship to be “a phenomenon that is characterized by systemic change in which under-represented people are able to access entrepreneurship opportunities and secure livelihoods, thereby leading to enhanced social inclusion and sustainable economic growth.” Key elements of the change we wish to see have been captured in a chapter in the State of India’s Livelihoods Report titled “India Needs to Move from Microenterprise Schemes to Building an Inclusive Entrepreneurship Ecosystem”1. They include a fundamental shift from “vertically” designed and managed enterprise development programmes to “horizontally” organized support systems. These systems would be based on stronger collaboration among all actors at the meso-level, the ability to co-create entrepreneurship solutions through collective intelligence born out of deep dialogue and the breaking down of social and institutional barriers. The positive results of the efforts would be seen in emergent, responsive and purpose driven enterprise support systems. Perhaps not possible a decade or two ago, breakthroughs in digital technology and new channels of communication make it possible to do so. More fundamentally, a new way of thinking and radically different inclusive entrepreneurship ecosystems would need to be put into place to set up a million new businesses in rural India every year. Changes would be needed at three levels – the extent of innovative and collaborative behaviour exhibited by various actors, enabling support made available by the entrepreneurship ecosystem and the larger policy architecture. If instituted, the changes would make public policy driven initiatives considerably more effective in accelerating economic growth and social inclusion. The benefits of “scaling-out” and “scaling-deep” across all sections of society at the grassroots would soon be reflected in the fulfilment of India’s goals for sustainable development, which it is now evident, are not attainable by relying only on scaling-up approaches. Internalizing this vision of a paradigm shift – in which narratives of entrepreneurship move from a linear, top-down, directed approach for ‘target fulfilment’ in enterprise development to systemic responses aimed at unleashing entrepreneurship at scale through a multitude of micro-movements – across actors is, we believe, an essential milestone toward engineering transformation at scale. Hence, our emphasis on building evidence which, we hope will make an irrefutable case for mainstreaming inclusive entrepreneurship. ■ Endnote: 1 Patara, S., Verma, K., & Chopra, V. (2021, January). State of India’s Livelihoods Report 2020. ACCESS Development Services.

Shrashtant Patara

|