|

Making Development a Good Business Ashok Khosla To achieve a sustainable future, India clearly has two priorities that must come before all others. The first is to ensure that all its citizens have access to the means of satisfying their basic needs. The second is to evolve practices that bring the environmental resource base back to its full health and former productivity. To achieve these two primary goals requires, as has often been reiterated in these pages, action on two fronts. We must:

Creation of livelihoods and jobs should, generally, be the job of the private sector. This has not been the case in post colonial India – there are today more than 20 million people working for government and public agencies, while less than 10 million workers are employed in "organized" or "formal" industries. These 30 million are the jobs to which the largest part of governmental decision making and attention are devoted. Yet, both these numbers are dwarfed by numbers of workers employed in the SME and "informal" sector in urban areas – some 110 million and in agriculture – some 240 million. And these, in turn, are dwarfed by the numbers of those basically out of work, which is the rest of the labour force – some 250 to 300 million. Private sector, in its restricted meaning of large corporate houses, or even the organized sector, is not currently geared to creating the jobs or livelihoods in the numbers needed in our economy. Besides, as has been repeatedly demonstrated by the work of Development Alternatives, the technology, financial and marketing imperatives of the bigger businesses operating in a globalizing economy make it unlikely that they will ever be in a position to do so. In the meantime, governments at all levels have, despite the temptations to the contrary, begun to show tendencies to cut back gradually on their payrolls. Somebody else, then, will have to take responsibility for creating sustainable livelihoods. This is the private sector in its larger meaning: entities that can be big but are mostly small, which work as businesses with profit as the main driving motivation. Encouraging widespread adoption of sustainable lifestyles needs the concerted efforts of all our leaders – the decision or opinion makers in government, business, media, schools and universities, voluntary organizations and, not least, the institutions of religion and faith. Since neither those who run government (of whatever political party or administrative cadre), nor those in business have shown much inclination to provide such leadership, it must come from the others – the "Civil Society". Although civil society hasn’t, so far, fared much better in delivering the results needed than either government or business, it still offers some hope and could serve as an effective entry point onto the road to building a better and more equitable future for our country. By providing strong leadership, civil society could, in principle, become influential enough to have a positive impact on even the public and private sectors. While we wait for such leaders to emerge, however, there are things that can be done by any one of us. Each citizen can, given a reasonable level of desire and commitment, start the process of creating both sustainable livelihoods and sustainable lifestyles on some meaningful scale. With enough of us doing so, a collective momentum will be built up to carry it forward into a nationwide process. What this needs is new kinds of institutions – a kind of marriage between the small private sector and the civil society. We like to call entities of this type "sustainable enterprises", organizations that have social objectives and business like strategies. Others call them, perhaps more descriptively, "social enterprises." Both of the primary national objectives listed above — sustainable livelihoods and sustainable lifestyles — are also best met by the same sustainable enterprises – small, local, environmentally benign businesses that create jobs and generate products and services in the community. Such enterprises are usually technology based, employ a small number of workers and highly profitable. In size, they lie roughly between the realm of what is called in official terminology as "small or medium enterprises" at the top end and "micro enterprises" at the bottom. The rural market has its own logic. It cannot be judged by the standards or frames of reference derived from the performance of other markets. In their terms, it is a complete and somewhat inexplicable paradox: vast latent demand, huge potential supply capacity, low level of transactions. Some numbers highlight the magnitude and complexity of this paradox.

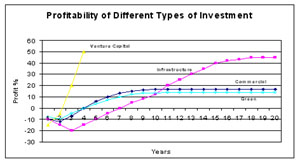

To succeed in this marketplace, a sustainable enterprise does require support systems of many kinds. It needs to carry out market research and develop a business plan. It needs to choose, acquire and master complex technologies. Once it goes into operation, it needs technical support to keep these technologies in good shape. It requires financing for fixed and working capital. It needs help in creating markets for its products. Such full spectrum support systems for sustainable enterprises are largely missing in the Indian economy. Thus, one of the key elements in any effective strategy to deploy and nurture sustainable enterprises is the establishment of support (or "mother") organizations that can provide, directly or through aggregation of available inputs from others, integrated services that are needed to make the sustainable enterprise profitable. To help its partner enterprises succeed in the marketplace, such a support organization must be able to provide highly sophisticated services involving complex technologies and support systems. It also needs the highest levels of innovation and implementation – which in turn involves the very best in creativity and management expertise. All these things are expensive and raise the cost of doing business, since sooner or later these costs will have to be passed on to the enterprises and thence to the end customers. But herein lies a fundamental contradiction: the end customers served by such an enterprise have very limited assets or purchasing power. The cost in a localizing economy After all, the very best in creativity and management expertise comes at a price – a price today determined by the interplay of economic forces in the so called global economy. Mechanical engineers, software designers and MBAs are, nowadays, commonly starting their careers with salaries approaching $ 30,000 a year, even in an economy like India’s; and twice that on overseas assignments. The cost of office space, computers, equipment, travel and other operational expenses is comparable to that in industrialized countries, and often higher. And these are the kinds of costs faced by any meaningful initiative to create sustainable livelihoods and implement programs to bring them in large numbers to rural India. It is not only that the cost of creating products needed in the countryside is high. The cost of delivering them is even more exorbitant because of inadequate infrastructure: few roads, little power and no connectivity. The rural customer faces a market in which already expensive products are made even more expensive because of the lack of infrastructure – most of which has been made available at public expense to her urban counterpart at virtually no charge. An Internet facility like TARAhaat, which wishes to cater to the needs of the rural public (which does, after all constitute three quarters of the country’s population) has often to include the costs of generating power and establishing connectivity in the business plan, infrastructure that is available at little or no cost in the city. In the industrialized economy, the prices commanded by the outputs of activities based on such costs can easily be paid by customers, who also earn comparable incomes – that after all, is the basis of the closed loop of household incomes and corporate expenditures that is explained in Chapter one of every economics textbook. And, most of the infrastructure cost has already been paid for. Purchasing power in a village economy But in a rural economy like that of India, the customer earns less than $ 2 a day. Clearly, there exists a massive disjoint between the cost of the goods and services needed by the poor and the prices they can pay for them. A solution often suggested, not just by the private sector but also by many in public agencies, is that the rural market is best left alone until it has generated the purchasing power and been "given" the requisite infrastructure to attract purely commercial ventures to provide the products and services it needs. (Thankfully, the development economists of old, with their give-away approaches to redistribution are no longer credible, though the massive, boondoggle and pork barrel "poverty alleviation" programs of government have still to be dismantled). A variant of this is "let them move to the city." But, of course, these are no solutions at all: they are simply an admission of defeat. They are no better than consigning the rural poor to an oblivion of endless cycles of poverty-hopelessness-high fertility-poverty-whether in the village or in the city slum — out of which they can never emerge. Matching prices to purchasing power One possible solution lies in bringing the costs of delivering a product or service down to the lowest possible level. The second lies in passing only its incremental costs on to the consumer. The third lies, of course, in raising the purchasing power of the customer. In all three cases, the economics of the support or "mother" organisation becomes extremely important. The first solution is itself achieved by a combination of well-known business strategies: creating standardized products, franchising local production and delivery systems and building up high sales volumes. Within the constraints of the village economy, building up sales volume can only be achieved by discarding conventional theories about focus on a single product line. It is the "country store" or super market that supplies an adequately broad range of goods to bring in enough customers who spend (possibly small) amounts on a sufficiently large number of items, which can cover its costs of operations and thus survive commercially. In this case, it is the "economies of variety" that substitute for the economies of scale that do not exist in a small and limited market. Such volumes do take time to build up to and the business must have staying power. The second solution implies that any major investments, particularly those for infrastructure, such as roads, telephones, water and energy are paid for by public or other sources of funds and it is only the incremental cost that is passed on to the consumer. This is not an unusual approach: the rich and the city people get such services all the time: they do not have to pay directly for the capital costs, which are amortised into the cost of service provided. The third approach is embedded integrally in the concept underlying sustainable livelihoods: local enterprises create the jobs and thence the income needed to purchase the products they generate – the kind of economic bootstrapping cycle Henry Ford dreamt of, applied to the village. For local solutions to work, they need higher level support services: brand equity, technology and know-how, training, maintenance and marketing. These services cost money. So do all the front end investments into research, infrastructure, startup and operationalizing a business. Many of these business supports are available at little or no cost to urban industries. It is therefore justifiable to provide them for organisations that support rural industries too. Consequently, the customer faces only the downstream recurring costs of production and distribution - probably the only type of subsidy that can be justified on any ground. Both solutions need public resources for the capital investments so that the incremental costs of each unit of product or service can be brought down to a level that is affordable to the buying public. This means we must learn to adopt different time horizons, financing instruments and profitability expectations from those of today. After all, even in the US with far higher purchasing power among its consumers, rural infrastructure such as electrification was achieved with financing at 1-3%, with repayment moratoria of several years and breakeven expectations of 20-40 years. And they need private sector inputs, too: operational financing, management efficiency and the ability to deliver results. In the longer run, realistic business analysis shows that even the dispersed rural market can provide commercially viable opportunities for many types of products and services. Integrating the Public and the Private This is why Development Alternatives and its affiliates such as TARA and TARAhaat have found it necessary to mix the public and the private, a pure anathema in conventional institutional design. The breakthrough lies in clearly separating the objectives from the strategies. In addition to commercial viability, the objectives for such an enterprise are primarily social, environmental and developmental. The strategies and methods used to achieve them, on the other hand, are purely business. And that means we need sources of capital that can accept longer time horizons for achieving profitability and possibly lower profits than are sometimes available in the market. The chart (given below) shows how the expectations of different types of investors vary. Conventional venture capitalists are primarily interested in very high and very quick returns. Their normal mode of operation is to put equity and loans at the disposal of entrepreneurs with a business plan that promises almost immediate return. As soon as the market value of the business reaches a few multiples of the original investment, the venture capitalist sells his or her shares at a significant profit. High return industries such as high technology or high value resource processing are the primary targets for such investments.

which is usually expected to be around three to five years. And "green" or "socially responsible" investors also expect good returns on their investments, but are prepared to accept somewhat longer time horizons and take lower dividends.Clearly, in the early stages of development ventures of the "mother" or support variety, such financing is more likely to come from public agencies, development banks and green investors than from venture capitalists. Indeed, there is considerable justification for initial funding in the form of grants and donations, since the earning capacity in the first, establishment, phase can only be very small. But, given the potential size and voracious appetite of this market, venture capitalists with a little imagination and a longer view would find all the returns they could wish for by investing in it. q |