|

The Social Enterprise:

Civil Society's Role in Creating

Wealth

Ashok Khosla

T he

central goal for any developing country today, as for an

industrialized one, is sustainable development. And that means a

more equitable and socially just development that is in harmony with

the natural environment.

A Dismal Scenario

Unfortunately, with the present economic model, it will be a long

time before this happens. The perceived logic of competing in the

global economy leads to the adoption of industrial production and

marketing systems that favour accumulation of wealth, mining of

natural resources and minimization of labour costs. These in turn

tend to increase disparities – between the rich and the poor,

between the cities and the countryside and between the men and the

women – rather than reduce them. Passive reliance on a hoped-for

"trickle-down" has never by itself been sufficient enough to reverse

the process – the ceiling of the income distribution usually rises

much faster than the floor. Economies that have succeeded in raising

the floor as well have done so by introducing strong measures to

ensure a more equitable distribution of the benefits of

socio-economic development. They have done this not through handouts

and charity but by enabling the creation of widespread opportunities

for livelihoods and jobs at all levels and

|

| Self employment

is the key to

empowerment |

nurturing these by

providing the necessary infrastructure, capacity building and

support systems.

Successive governments in India,

prodded by parliaments with their own

electoral compulsions have been quite generous with so-called

"poverty alleviation programmes". These allocate a sizable portion

of the national budget for various services ostensibly directed at

helping the poor, although the actual amounts are tiny compared with

what is being spent on government and other public sector salaries,

pensions, and various subsidies of interest primarily to those above

the poverty line. Moreover, the bulk of these funds are of the

handouts and charity variety – and even of these, only a small

fraction actually goes into producing the results that they were

intended for. Very few of our political leaders have tried to

introduce the much more needed, but much less obvious, interventions

required to create livelihoods and jobs. Even fewer have created the

frameworks to generate such livelihoods and jobs on a sustainable

basis.

Need for a New

Approach

The eradication of poverty needs very different approaches. First,

of course, it needs some deep structural

changes in society: grass roots democracy, land reform, access to

livelihood resources and fulfillment of everyone’s right to

reasonable education and health care. Bringing about such change,

even with a major struggle to overcome the opposition to it from the

rich and powerful requires time. Bihar is the archetypal

demonstration of this, but the prognosis is not much better in other

states. In the meantime, it is also worth mounting an attack on

poverty within the existing systems, highly resistant to change

though they may be, to remove at least the most extreme forms of

inequity.

Only thus can the poor position themselves in society to start

asserting their rights and getting them. The instruments needed to

achieve this are far more sophisticated and complex than any

available in today’s one-dimensional economic systems. And that

means we need the highest levels of innovation and implementation–

which in turn requires the very best in creativity and management

expertise.

In India, as in many other countries, the key strategy to achieve

sustainable development must be through the creation of jobs – and,

in particular, jobs of a specific kind.

Sustainable Livelihoods

We need jobs that produce, at a minimum, the goods and services

required to fulfill everyone’s basic needs. These are jobs that at

the same time generate the widespread income – and therefore the

purchasing power – necessary to give people access to these goods

and services. Such jobs regenerate, rather than destroy, the

environment and its resources. Because of the contribution they can

make to economic efficiency, social equity and environmental

quality, such jobs are today called sustainable livelihoods – best

created by very small, local, eco-efficient businesses or

sustainable enterprises

Sustainable livelihoods are

particularly suited to the needs of women, the poor and the

marginalized. By providing people with income and some degree of

financial security, they are an excellent means of empowering people

within their communities. Most important, together with programmes

for education of girls and women, sustainable livelihoods are

probably the most effective stimuli for smaller families and lower

birth rates.

India now has to create

sustainable livelihoods on a large scale. The capacity of

agriculture to absorb more labour is rapidly reaching a plateau. To

close the unemployment gap by the year 2015, India will need to

create 12 to 15 million jobs off the farm — each year. "Modern", big

industry is not capable of creating this

many workplaces. Today, it can hardly create two million jobs per

year.

Economic Growth

The second, and not unrelated, goal for a country like India clearly

is to accelerate the rate of growth of the economy. While the

nation’s planners debate whether this rate should be 7% or 8% per

year, eradication of poverty within a reasonable time frame will

need growth rates in the double digit region. China has demonstrated

that such a growth rate is not only possible, but that it can be

sustained over long periods.

The reasons for both failures lie, ironically, in the very structure

of industrial production that has provided so many benefits for so

many people all over the world: its emphasis on mechanization,

centralization, large scale, and use of energy guzzling and material

intensive technologies. The imperatives of competitiveness in the

global economy encourage the choice of particular types of

production systems. They are mostly complex and expensive. The

technology used is generally capital intensive and labour

displacing; the fossil fuels, raw materials and components are often

imported and their availability uncertain; and the management

systems required are sophisticated and costly. Such systems need

large investments have long start-up gestation periods and create

few jobs.

In small and mini plants, the scarce capital is recovered in a much

shorter time, making it possible to reinvest it in further

production and job creation. The capital cost of creating one

workplace in the modern industrial sector in India is well over $

100,000 – often including a significant component of imported

technology and equipment. At this rate, just the creation of twelve

million jobs each year would by itself would cost four to six times

the GNP of the country. It simply cannot be done.

Clearly, a better mix of large, small and mini industries is now

needed. Given the continued failure of policies to address the needs

of the small, mini and micro sectors, a proper balance will require

greatly enhanced encouragement and incentives to such industries.

There are, of course, sectors for which the economies of scale favour large, mechanized production units. These probably include

steel making, oil refining, petrochemicals and automobile

manufacture. But, there are many sectors where economies of scale

are not relevant. Most industries producing basic goods for rural

populations are commercially viable even at quite small scales. And

because of the low capital requirements, they can have high returns

on investment – in some cases even double those for their larger

counterparts.

Indeed, if the full economic and environmental cost of the processes

and resources used in manufacturing and delivering products is taken

into account and no "perverse" subsidies are allowed for energy,

transportation, financial and other services, small scale production

can become quite competitive.

As an evidence of this, "small and medium enterprises" already form

the backbone of the national economy. They account for more than 60%

of the industrial production in India, and for more than 65% of

industrial exports. They account for more than 70% of the industrial

employment. When adjusted for the vast subsidies and infrastructure

that large scale industry can take advantage of, their real

contribution to the economy is even higher.

Sustainable enterprises are usually quite small. They have between

one and 100 employees, with an average around 20. They are generally

informal and flexible and quite labour intensive. However, being

small, dispersed and largely unregulated, mini enterprises can often

have environmental and social impacts that are fairly negative. To

overcome this, they need access to better technologies as well as

other supports.

Many technologies for such enterprises already exist. So does the

demand for their products. What prevents the poor from setting up

such enterprises is their lack of access to these technologies and

their inability to put together the financial capital required. What

prevents them, once set up, from becoming profitable is the absence

of entrepreneurial and management skills, infrastructure and

marketing channels. Much more public investment is needed to provide

these, but probably not nearly as much as is being made today for

the benefit of large, urban industries.

Several mechanisms are now evolving to help enterprises overcome the

barriers to obtaining technology, to using effective transport and

communication facilities and to introducing modern management

methods. But, credit continues to be the key missing link.

Currently, finance is fairly easily available to "small and medium

enterprises" that have capital requirements of Rs. 10 lakhs ($

25,000) or more. Also, increasingly available is finance to micro

industries that need capital of less than Rs.10, 000 ($ 250).

Mini Enterprises

However, it is precisely

the mini enterprises that fall in the range between these two

categories, with capital investments of Rs 10,000 to Rs. 10 lakhs,

which optimize the twin objectives of sustainable livelihoods and

returns on investment. They are small enough to be responsive to the

local economy yet large enough to employ technologies and skilled

workers and to maximize labour productivity. At the same time, they

are big enough to take advantage of public infrastructure, credit

facilities, technology support and marketing channels, provided

these are available. There are numerous technology-based mini

industries in this range that could be set up today and run

profitably.

Such enterprises can create, directly, several workplaces, each at a

capital investment of Rs.20, 000 to 50,000. In addition, they

indirectly lead to the creation of several more jobs (Upstream or

downstream), usually at an even lower capital cost. Such workplaces,

in the village or small town, yield incomes for workers whose

purchasing power is comparable to, if not better than, those created

at hundred times the cost in large urban industries. At the same

time, they permit very high returns on investment, sometimes with

payback periods of less than a year.

The paradox of our economy is that there is virtually no source of

funding today that can actually deliver adequate financial credit in

this intermediate range (which might properly be termed "mini

credit") where it has greatest potential impact, both on the

generation of employment and on the national economy. Nor are there

any support systems to provide technological, managerial or

marketing inputs to help them become profitable. It is here that new

kinds of civil society organizations – "social enterprises" – are

needed. These enterprises are themselves not-for-profit but serve

the purpose of creating widespread wealth through the creation and

sustenance of large numbers of mini-enterprises.

Creating livelihoods and jobs is not the job of government. Despite

its cancerous growth to the 20 million employees and 15,000 crore

yearly pension bills it has at present, the real role of governments

is to govern: to set policies and to facilitate the orderly

performance of the other sectors – whose job it is to create jobs

and deliver services. Establishing the conditions under which

livelihoods and jobs are easily and plentifully created is the job

of government. To create such conditions, governments should have

their hands full designing and implementing policies, fiscal

measures, institutional frameworks and all other means that

encourage other sectors to produce the goods and services people

need and to generate the incomes with which they can fulfill

these needs these needs.

Creating livelihoods and jobs should largely be the job of the

private sector. Unfortunately, large businesses have not

demonstrated the ability or willingness to do this job. In the

twelve years since the introduction of economic liberalization, the

number of jobs in the formal private sector has actually gone down.

Today, the formal sector employs less than ten million people – less

than two percent of the country’s workforce.

Jobs in India, as in all other economies, are actually created by

the small and medium (SME) sector, by the "informal" sector and –

most of all — by the mini and micro enterprises that dot the

countryside. Since rising productivity in agriculture means that the

bulk of the 15 million livelihoods and jobs we need to put in place

each year will have to be off-farm, it is these sectors that will

have to take responsibility for getting our country to work.

The largest potential for livelihood creation, particularly for

women and the marginalized, lies in the mini and micro enterprise.

Micro enterprises, with one to five workers, and a capital

investment of ten thousand rupees or less are suited to household

industries that largely produce items for use in the local

community. Mini enterprises, with five to fifty employees (and

capital investments of several lakhs) are capable of using

technology and marketing methods to reach beyond the needs of the

local community and generate surpluses that enable them to grow and

invest in further growth.

To be successful, micro and mini enterprises need a variety of

support systems. And herein lies a fundamental contradiction.

Costs in a localized

economy

After all, the very best in

creativity and management expertise comes at a price – a price today

determined by the interplay of economic forces in the so called

global economy. Mechanical engineers, software designers and MBAs

are, nowadays, commonly starting their careers with salaries

approaching $ 30,000 a year, even in an economy like India’s; and

twice that on overseas assignment. The cost of office space,

computers, equipment, travel and other operational expenses is

comparable to that in industrialized countries, and often higher.

And these are the kinds of costs faced by any meaningful initiative

to create sustainable livelihoods and implement programs to bring

them in large numbers to rural India.

It is not only that the cost of creating products needed in the

countryside is high. The cost of delivering them is even more

exorbitant because of inadequate infrastructure: few roads, little

power and no connectivity. The rural customer faces a market in

which already expensive products are made even more expensive

because of the lack of infrastructure – most of which has been made

available at public expense to her urban counterpart at virtually no

charge.

An Internet facility like TARAhaat, which wishes to cater to the

needs of the rural public (which does, after all constitute three

quarters of the country’s population), has to include the costs of

generating power and establishing connectivity in the business plan,

factors that are available at little or no cost in the city.

In the industrialized economy, the prices commanded by the outputs

of activities based on such costs can easily be paid by customers,

who also earn comparable incomes – that after all, is the basis of

the closed loop of household incomes and corporate expenditures that

is explained in Chapter one of every economics textbook. And most of

the infrastructure cost has already been paid for.

Purchasing power in a

village economy

But in a rural economy like that of India, the

customer earns less than two dollars a day.

Clearly, there exists a massive disjoint between the cost of the

goods and services needed by the poor and the prices they can pay

for.

A solution often suggested, not just by the private sector but also

by many in public agencies, is that the rural market is best left

alone until it has generated the purchasing power and been "given"

the requisite infrastructure to attract purely commercial ventures

to provide the products and services it needs. (Thankfully, the

development economists of old, with their give-away approaches to

redistribution are no longer credible, though the massive,boondoggle

and pork barrel "poverty alleviation" programs of government have

still to be dismantled). A variant of this is "let them move to the

city." But, of course, these are no solutions at all: they are

simply an admission of defeat. They are no better than consigning

the rural poor to oblivion of endless cycles of

poverty-hopelessness-high fertility-poverty – whether in the village

or in the city slum — out of which they can never emerge.

Matching prices to

purchasing power

One possible solution lies

in bringing the costs of delivering a product or service down to the

lowest possible level. The second lies in passing only its

incremental costs on to the consumer. The third lies, of course, in

raising the purchasing power of the customer.

The first solution is itself achieved by a combination of well-known

business strategies: creating standardized products, franchising

local production and delivery systems and building up high sales

volumes. Within the constraints of the village economy, building up

sales volume can only be achieved by discarding conventional

theories about focus on a single product line. It is the "country

store" or super market that supplies an adequately broad range of

goods to bring in enough customers who spend (possibly small)

amounts on a sufficiently large number of items, which can cover its

costs of operations and thus survive commercially. In this case, it

is the "economies of variety" that substitute for the economies of

scale that do not exist in a small and limited market. Such volumes

do take time to build up to and the business must have staying

power.

For local solutions to work, they need higher level support

services: brand equity, technology and know-how, training,

maintenance and marketing. These services cost money. So do all the

front end investments into research, infrastructure, startup and operationalizing a business. Many of these business supports are

available at little or no cost to urban industries. It is therefore

justifiable to provide them for rural industries too. Consequently,

the customer faces only the downstream recurring costs of production

and distribution – probably the only type of subsidy that can be

justified on any ground.

Both solutions need public resources for the capital investments so

that the incremental costs of each unit of product or service can be

brought down to a level that is affordable to the buying public.

This needs different time horizons, financing instruments and

profitability expectations from those of today. After all, even in

the US (with far higher purchasing power among its consumers), rural

infrastructure such as electrification was achieved with financing

at 1-3%, with repayment moratoria of several years and breakeven

expectations of 20 to 40 years.

And they need private sector inputs, too: operational financing,

management efficiency and the ability to deliver results. In the

longer run, realistic business analysis shows that even the

dispersed rural market can provide commercially viable opportunities

for many types of products and services.

This is why Development Alternatives and its affiliates such as TARA

and TARAhaat have found it necessary to mix the public and the

private, a pure anathema in conventional institutional design. The

breakthrough lies in clearly separating the objectives from the

strategies. In addition to commercial viability, the objectives for

such an enterprise are primarily social, environmental and

developmental. The strategies and methods used to achieve them, on

the other hand, are purely business. And that means we need sources

of capital that can accept longer time horizons for achieving

profitability and possibly lower profits than are sometimes

available in the market.

The

Development Alternatives was recently selected for the Karl Schwab

Foundation’s Outstanding Social Enterprise Award for 2004.

q

|

The Gift of Recycled

Paper |

|

|

Recycle paper.

It saves life. And it helps to protect our fragile life support

systems.

Forests are among the richest expressions of life on our planet.

Trees are, of course, the most visible part of a forest. But the

other living things that depend on the habitat they create are

just as important: the animals, the birds and the insects — and

the flowers, the plants and the fungi. And none of these could

survive without the tiny lichens and spores and microbes that

ultimately drive the very engine of life.

Each of

them is valuable for the key role it plays in the ecology of the

forest – for its contribution to the health of the forest and to

the well-being of all its inhabitants. Each is necessary to

weave the rich tapestry of forest life which is the source of so

much of our foods, fuels, fibres and fertiliser — not to mention

medicines, spices and large numbers of livelihoods.

And, of course, each has a right to life of its own, whatever

its utility to the economy.

When we

cut down the trees, all these living beings are destroyed. And

so are the life supports on which we depend: the ground water recedes,

the soil erodes

and the

amount of deadly carbon dioxide increases in the atmosphere.

When we

pollute our rivers, we also destroy myriads of other living

things and undermine equally important life processes.

Recycling of

paper, by using wastes – used paper, cotton rags and unwanted

biomass – saves trees and minimises pollution. No cutting of

trees and no chemicals in our water courses mean that use of

recycled paper saves both our forests and our rivers. And,

naturally, it saves the life that teems in them.

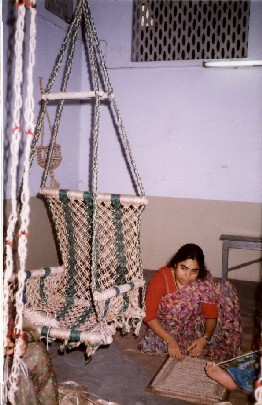

TARA

paper is particularly special. It is not only made of recycled

and waste materials: it is crafted by the careful hands of

highly skilled villagers, most of whom were impoverished women.

It creates jobs and incomes while saving the environment.

Remember! One tonne of TARA paper saves 3 tonnes of wood and 100

cubic metres of water – and creates

Rs. 40,000 in wages, giving us:

| l |

6 trees for life-giving oxygen, soil and water |

|

l |

3 years of cooking fuel for one village family |

|

l |

25 years’ drinking water for one person |

|

l |

1 square foot of land for a waste dump site and |

|

l |

1 month’s income for 20 village women |

Use TARA — The Eco-friendly

Paper

Use TARA — The Eco-friendly

Paper

For details, please contact:

The Business Manager

Technology and Action for Rural Advancement (TARA)

B-32 Tara Crescent, Qutab Institutional Area, New Delhi - 110

016, INDIA

Tel: +91-11-685-1158, 696-7938

Fax: +91-11-686-6031; Email: tara@sdalt.ernet.in

|

|

|