|

Functional Literacy for

Better

Literacy, whether achieved as the

core of schooling in childhood or through learning later in life, is the

passport that allows an individual to participate in contemporary

social, economic and political development. Literacy refers to an

individual's ability to communicate through reading and writing.

According to UNESCO, there are 771 million illiterate adults in the

world. Nearly half of these live in South Asia, where illiteracy is

still largely a female phenomenon. In India, the adult female literacy

rate (over 15 years) is 59 percent versus 79 percent for men (WDI, data

from 2011). There is considerable optimism about India’s recent economic

progress. However, India’s progress in terms of adult literacy and

lifelong learning has been a big of mixed successes. On the positive

side, there has been a substantial shift and increase in adult literacy

rates, from 61% in 2000 to 72.2 % in 2015. On the negative side, India

is still home to a considerable 340 million illiterate adults, 172

million of them being women. Even after more than half a century of

independence, there exist marked disparities within India, which make

some sections of the population highly vulnerable. In addition to the

rural-urban divide, the caste, class and gender disparities result in

many people of one country living in vastly different worlds in terms of

health, education and other development indicators. Progress of adult

literacy in India has too been considerably affected by such

disparities. Given that 37 percent of illiterate adults are in India

(UNESCO, 2014), the evidence from India is critical in terms of our

understanding of the broader, intergenerational impacts of adult female

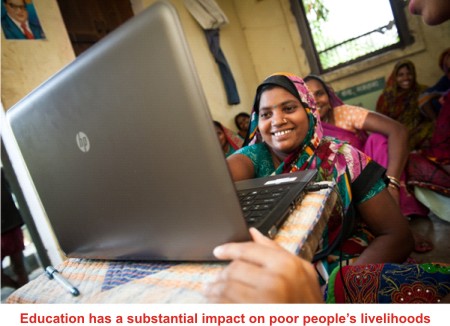

literacy. The intersection between training in livelihood skills and basic education for illiterate and semi-literate youth and adults has also not been explored to a desirable extent. Questions like whether effective training in livelihood skills be developed as an add-on to large scale literacy programmes or whether combinations of livelihood skills training and adult literacy education help improve poor people’s livelihood continue to remain unexplored and unanswered to a large extent. Discussions of Education for All often tend to neglect the question of vocational education for illiterate adults. Organisations that specialise in vocational training – FAO and ILO - recognise that literacy and numeracy are essential for workers to increase their productivity and incomes. Is literacy a prerequisite in preparation for training in livelihood or income-generation activities or can livelihood programmes run separately from literacy programmes and have the desired effect also necessitates answering. This article tries to answer these questions, stressing upon how literacy education and skill development have a substantial impact on poor people’s livelihoods, while trying to establish how literacy programmes need to be coupled with components of livelihood preparedness and livelihood skills to have the desired effect, citing learnings from Development Alternatives’ flagship adult literacy programme, TARA Akshar+.

TARA Akshar+ functional literacy programme for adults is not merely a

delivery of functional literacy to women, but also has components of

livelihood preparedness and livelihood skills, including health

awareness and financial literacy. This combination of literacy and

livelihood preparedness has demonstrated changes in the livelihood

patterns of its learners. Firstly, there is a widely noted ‘empowerment

effect’ - that learners acquire enhanced confidence and social resources

which help them take initiatives to improve their livelihoods. Second,

literacy and numeracy skills are a clear advantage in market

transactions in an informal economy like India. Then, there is the

creation of a sense of identity for the learners, a feeling of becoming

self-reliant, within their households and communities. Based on personal experiences and reviews, it has been observed that TARA Akshar+ participation does result in significant impacts on the mechanisms which underlie the theory of change. The women have increased general knowledge of health and educational matters, increased confidence in dealing with people outside their families and increased self-confidence. Within the households, the women now were more likely to be exempted from seeking permission to leave the house. While making decisions with their spouse, there is an increased probability that the women would be consulted and not dictated. The writer attributes these impacts to primarily two aspects of TA+. TA+ enabled the women to move out of the house to assemble at a central location to attend the classes and to interact for a longer time with people outside their family. A more important aspect of TA+ is the complementary discussions on a wide variety of topics which have proved extremely influential for the women learners. As a recommendation, it would be important to have these two aspects in place for any adult literacy programme, complementing the literacy and numeracy components, and bridging the connect between literacy and livelihoods. It has also been noted during the delivery of this programme that literacy is a prerequisite in the preparation for imparting livelihood skill or income-generation activities. It has been observed, basis interactions with the learners and beneficiaries of the TARA Akshar+ programme that training in livelihood skills and income generation is the longer-term aim, but people are encouraged not to start training in a livelihood, until they have first mastered reading, writing, and calculating sufficiently to cope with the livelihood’s operating and development requirements. There is a planned progression between the two. It has also been observed, however, that leaners are also not merely satisfied having acquired functional literacy and demonstrate a continued need and desire for skill building and livelihood training to enhance their income-generation abilities. Experience from these learnings has produced a strong consensus that literacy programmes and livelihood skill programmes separate from each other are not as successful as ones that have the necessary components of both. Learners feel more comfortable while acquiring livelihood skills if they can read, write and do simple arithmetic. However, literacy programmes that have content of literacy derived from or influenced by the livelihood appeal more to the learners as they can, after all, demonstrate an immediate reason for learning. Literacy programmes aimed at adults must go beyond the teaching of reading, writing, and arithmetic. They must teach adults, especially women, to become self-reliant, make sound decisions concerning their lives, protect the environment, promote the health of their families and support their children's education. However, programmes aimed at promoting adult female literacy have been hindered by factors such as lack of free time and child care, religious traditions that restrict women's activities to the domestic sphere and husbands' concerns about female autonomy. To be successful, such programmes must obtain community support, adopt an integrated approach that meets women's immediate needs, make post-literacy training available, link the literacy project to community development and ensure women's participation at each step of programme formulation and implementation. Literacy efforts concerned with meeting women's practical needs should be paired with activities aimed at long-term strategic interests, including income generation, formation of indigenous women's organisations, health care, conservation of natural resources and adequate housing. Finally, available research, personal experiences and reviews, have indicated that adult literacy programmes are most successful when instructional technology is accompanied by a social ideology aimed at empowering women, but it also must have long-term strategic interests, like income-generation and livelihood preparedness at the heart of the curriculum of such literacy programmes. ■

Akash Vohra |