|

The

Challenge of LCA

A Tool

for Green Evolution |

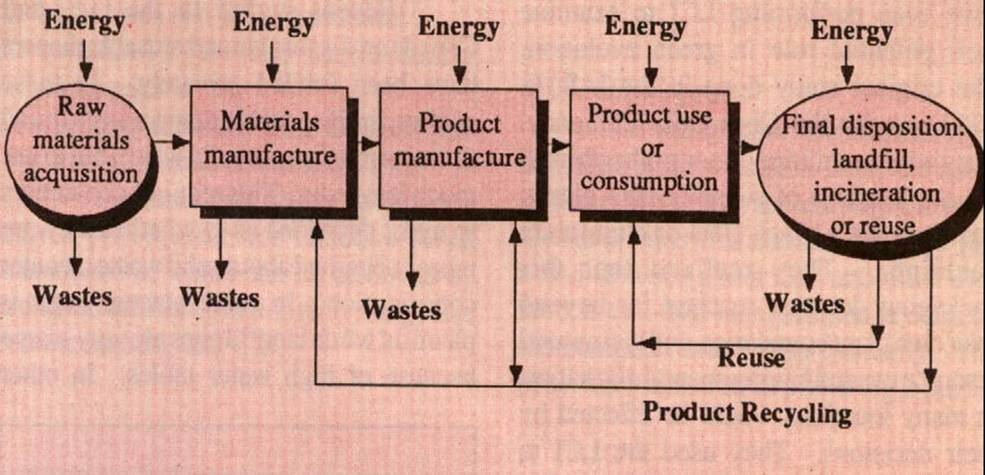

Environmental Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) is a tool that has been used for 24 years to bring more scientific knowledge into the complex process of making decisions. The idea of LCA originated with the realisation that consumer purchases of products (and services) sets into motion a large and complex network of activities. Purchasing alternate products or selecting alternative ways to satisfy that consumer demand generally sets into motion an entirely different set of activities. The idea of LCA is that these entire networks are intimately related to consumer activities. The interconnected activities are illustrated in Figure 1, which is a highly simplified representation. In fact, even relatively simple systems may have 40 or more processes which contribute significantly to the total system.

Consumer practices are not the only mechanism of creating environmental

improvement through the use of LCAs. Another important the use of LCAs.

Another important way that these production networks can be improved is by the

voluntary action of the various industrial and commercial operators that own

and operate the various processes. This is particularly effective when major

operators seek to improve the end product by a combination of improving their

own operations as well as exerting influence on their suppliers through

purchasing decisions. In the U.S., this has been the major use of LCA.

environmental

improvement through the use of LCAs. Another important the use of LCAs.

Another important way that these production networks can be improved is by the

voluntary action of the various industrial and commercial operators that own

and operate the various processes. This is particularly effective when major

operators seek to improve the end product by a combination of improving their

own operations as well as exerting influence on their suppliers through

purchasing decisions. In the U.S., this has been the major use of LCA.

The concept of LCA is that environmental inputs and outputs can be identified for each of the parts of the system and somehow summed to find the total impact associated with each product or service. However, there are complexities and problems that interfere with the easy execution of this plan.

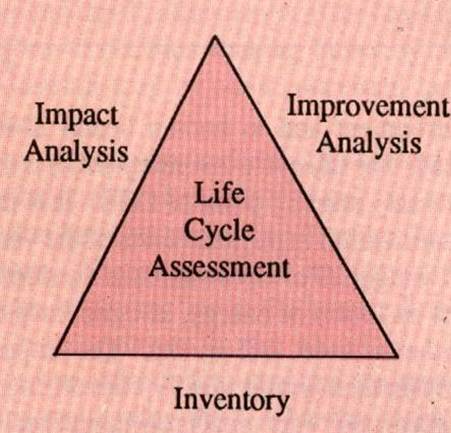

A three-part concept has been developed to illustrate how LCA can be accomplished. Figure 2 shows the triangle relationship of inventory, impact analysis and improvement analysis. The improvement analysis is the primary goal of LCA. This is where the LCA information can be used to improve product and service systems so that harm to the environment and to human health is reduced. The life cycle inventory (LCI) is the necessary starting point of LCA. It is the quantification in physical unit of the various categories of environmental concerns, such as Joules of energy, kilogrammes of carbon dioxide, and so on. The impact analysis then would ideally convert those physical units into impacts on human health and the environmental, such as excess cancer deaths cause by ozone depletion or increased incidence of asthma from particulate air pollution. This information then could be used to determine appropriate improvement strategies.

It is at the impact analysis stage that the system breaks down. At this time, there is no widely accepted method to conduct an impact analysis in a life cycle format. The problem is the inaccuracy in converting physical units into impacts. While many authors have proposed impact analysis theories, and many others have created examples of impact analyses, the fact remains that there is no scientific peer-reviewed method that has gained wide acceptance.

The

lack of dependable impact analysis methods is by no means a necessary

deterrent to the use of LCA in making decisions. Environmental improvement

can be planned by moving directly from life cycle inventories (LCI) to

improvement analyses. This is the reason for the triangle concept as shown in

Figure 2. At this time, most life cycle studies that have been produced are

LCIs, which are used for improvement planning and execution without benefit of

an impact analysis.

The

lack of dependable impact analysis methods is by no means a necessary

deterrent to the use of LCA in making decisions. Environmental improvement

can be planned by moving directly from life cycle inventories (LCI) to

improvement analyses. This is the reason for the triangle concept as shown in

Figure 2. At this time, most life cycle studies that have been produced are

LCIs, which are used for improvement planning and execution without benefit of

an impact analysis.

LCI cannot provide the answer that many people want. Most people want a comprehensive answer of “goodness” or “badness” of a product. However, LCI can provide answer only in those impact categories where the lack of impact categories factors is not a serious problem. Historically, the two primary areas for which this is true are energy and solid waste. Conversion factors exist that allow the natural resources use of energy to be reported in a common unit of joules. A similar situation exists with solid waste. The depletion of landfill space can be characterised in terms of cubic meters of space occupied. While the conversion factors for solid waste are not as accurate as for energy, they are acceptable. Water volume is another possible candidate for inclusion, although data for the depletion of water resources are not accurate in most case.

The goal of LCA, or LCI, activity is to plan and execute changesthat result in less damage to the environment and a reduction of health risk to humans. While almost all activities of people contribute in some way to environmental damage and risk to health, the goal is to establish a mechanism by which we can maintain continued improvements in lifestyle but at the same time reduce demands on our surroundings to a level which is sustainable for all time. The movement in that direction is called “green evolution”.

The challenge of using LCI for green evolution can be addressed at three levels: within a private company, for consumers of goods and services, and in response to regulatory concerns.

For over two decades, companies have been performing LCI to examine their potential role in green evolution. The original study done in the U.S. n 1969 was for the Coca Cola Company. They were examining (among other things) the implications of substituting a plastic container for a glass, steel or aluminium container. They realized that this packaging decision reached far beyond their own plant boundaries, and that natural resource use and environmental discharges in many locations would be affected by their decisions. They used the LCI to examine those implications.

The use of LCI has evolved over the years to a more sophisticated consideration of the role of private companies in affecting both upstream and downstream processes. Energy and solid waste have been the focus of these studies, using the tacit assumption that these are the important areas in which LCI can provide useful information. For example, one company recently established a goal of reducing the solid waste associated with their product. They wanted to reduce waste without increasing other ecological damage. An LCI of their product showed that increasing the recycled content of their raw material would achieve this goal. In this case, an impact analysis was not necessary to arrive at that conclusion. An LCI showed that the use of recycled materials resulted in less energy, less solid waste, and less pollution for the entire system.

LCI studies can provide consumers with information that will allow them to make better purchasing decisions. The original idea of LCI in the 1970s was that this would be a primary use of the methodology. Many studies have been directed towards this end. In 1973, a comprehensive study was commissioned by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to produce an LCI of nine beverage container alternatives. The expected result was to produce a data base that would allow a clear decision as to whether consumers should purchase beverage in refillable or disposable containers. However, the results showed that some recycling options led to results as favourable as the use of refillables in some circumstances. The results were complex, and it was not clear that any single beverage container option would be preferable in all cases. LCI results often cannot be reduced to a simple answer.

Recent studies in the U.S. and Canada on disposable and reusable diapers have been funded privately. In these studies, the disposable diapers were found to create much more solid waste, but to use much less water. This requires consumers to make decisions as to whether they are more concerned about solid waste or water consumption. In some places, water is plentiful while landfill sites are very scarce because of high water tables. In other locations, water may be in short supply while there is still landfill capacity to serve the community needs for many decades. This means that there is not a single answer as to which purchasing decision is the correct one for all people.

The third area of application and interpretation of LCI is the use by governments to regulate products and services. In the beverage container study mentioned above, the EPA decided, after lengthy deliberation, that using LCI was quite clumsy. To achieve significant environmental improvements, LCI would have to be done on many, if not all, products in the U.S. eventually. This was project of such monumental proportions that they sought other pathways to environmental improvement. They decided that it was more useful to focus on the specific ecological issue of concern. For example, if energy conservation regulations are more effective than the use of product selection to bring about reduced energy use.

Another disadvantage of LCI in regulatory applications is that the restriction of a free market results in changes which may have unforeseen effects in the long term. For example, if the EPA beverage container study had been used as a basis for regulation 20 years ago, if probably would have discouraged the use of aluminium containers. As a result, the recycling technologies that have developed would likely never have occurred, at least not in the time frame in which they developed.

The major regulatory thrust today for LCI is probably in ecolabelling. Unfortunately, many people believe that LCI can give a definitive answer for ranking products. While it is now becoming clear that impact analysis is not feasible, and that the use of LCA in labelling should be restricted to the few categories in which the LCI can give definitive results, there are still major efforts to include LCA in labelling considerations. It should be made clear that labelling activity that merely uses selected LCI data and subjective evaluations by panels or others is not an LCA activity that has scientific validity.

The challenge of LCA practitioners today is to learn how to use it as a tool for green evolution. The most effective use is by private companies, examining not only their own operations, but how their decisions affect the entire continuum of operations of which they are a part. LCA can also be used by consumers to make wise purchases and to create markets for those products which are more desirable when LCI calculations clearly demonstrate that one product makes less demands on the environment than others in all cases. However, often LCI results are so complex that easy decisions are not possible. In addition, the lack of general results on materials or classes of processes is a disadvantage to consumers or regulators.

At this point in time, only the LCI portion of LCA has scientific validity. Users should beware of the subjective nature of impact analyses for which there is no general agreement on validity by the scientific community.

(Robert G. Hunt of Franklin Associates Ltd.,

Kansas, USA,

presented this paper at the UNEP Expert Seminar organised last month by the

Centre of Environmental Science,

Leiden University, Amsterdam).

| Donation | Home | Contact Us | About Us |