|

Economics of Low Carbon Pathways D uring the last two decades, much capital was poured into fossil fuels and structured financial assets. However, relatively little in comparison was invested in renewable energy, energy efficiency, public transportation, sustainable agriculture, ecosystem and biodiversity protection and land and water conser vation. vation.

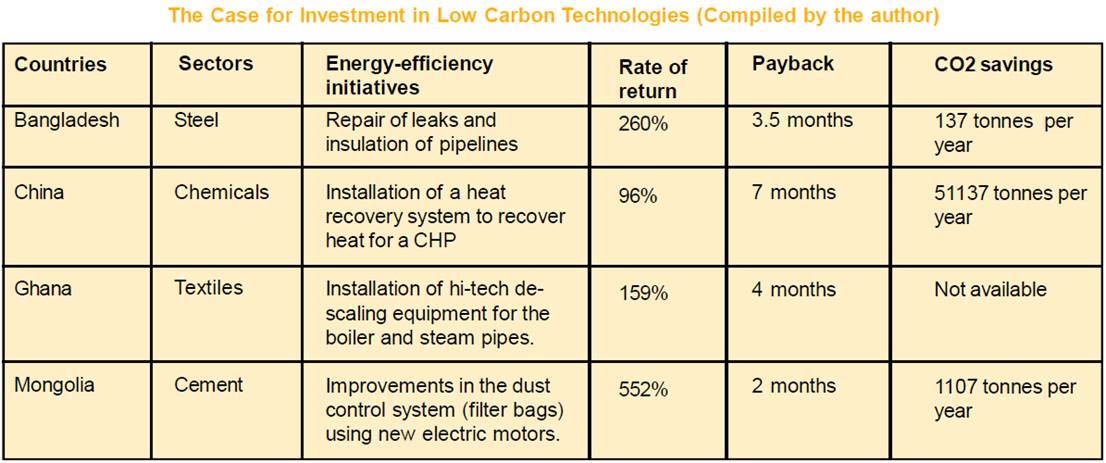

The Stern Review1 argues that the damages from climate change are large and that nations should undertake sharp and immediate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. The Review estimates that if we do not act, the overall costs and risks of climate change will be equivalent to losing at least 5% of the global GDP each year. If a wider range of risks and impacts is taken into account, the estimates of damage could rise to 20% of GDP or more. Inaction now and over the coming decades could create risks on a scale similar to those associated with the great wars and the economic depression of the first half of the 20th century. One of the major findings in the economics of climate change is that efficient economic policies to slow climate change involve modest rates of emission reductions in the near term, followed by sharp reductions in the medium and long term. This is called the climate-policy ramp, in which policies to slow global warming increasingly tighten or ramp up over time. The logic of the climate-policy ramp is straightforward. In a world where capital is productive, the highest-return investments today are primarily in tangible, technological and human capital, including research and development on low-carbon technologies. In the coming decades, damages are predicted to rise relative to output. As that occurs, it becomes efficient to shift investments toward more intensive emission reductions. Creating a transparent and comparable carbon price signal at the global level is an urgent challenge for international collective action. It is critical to have a harmonised carbon tax or the equivalent both to provide incentives to individual firms and households and to stimulate research and development in low-carbon technologies. Carbon prices must be raised to transmit the social costs of greenhouse gas emissions to the everyday decisions of billions of firms and people. Discounting is a major ethical factor in climate change policy. A zero time discount rate means that future generations into the indefinite future are treated symmetrically with present generations. A positive time discount rate means that the welfare of future generations is reduced or discounted compared to nearer generations. Choice of low discount rates magnifies impacts in the distant future and rationalises deep cuts in emissions and consumption, today. As countries are thinking of choosing a low discount rate when it comes to their climate change policies, the concept of ‘green economy’ is getting evolved. In its simplest expression, a green economy is a low-carbon economy which is resource efficient and socially inclusive. In a green economy, growth in income and employment are driven by public and private investments that reduce carbon emissions and pollution, enhance energy and resource efficiency and prevent the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Enabling Conditions for a Green Economy • Changes to fiscal policy, reform and reduction of environmentally harmful subsidies and employing new market-based instruments. • Public investments in green key sectors, greening public procurement and improving environmental rules and regulations as well as their enforcement. q Lalit Kumar Endnotes 1 Stern review, published in 2006, examines the economic impacts of climate change and explores the economics of stabilising greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. |