|

Participatory Management of

The mountain ecosystems of the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) are spread across 11 states, covering 3,000 km in length and 200-300 km in width. The significance of these ecosystems was first recognised internationally by the Rio Conference in 1992 wherein it was stated that 'the livelihood of about 10% of the world's population relies directly upon mountain resources such as water, forests and agricultural products and minerals' (Chapter 13: United Nations, 2001). Problem Statement: Depleting Mountain Community Stewardship in Managing Natural Resources Communities of the mountain ecosystems have played a crucial role in maintaining a sustainable flow of resources to the plains below. But in recent years, with the coming of new technologies, population increase and development pressures; the magnitude of this resource outflow has increased dramatically. Beneficiaries of the plain areas have contributed little to reinvestment in the management of the mountain natural resources. The mountain communities themselves have been marginalised. This has resulted in the loss of community stewardship for these mountain resources.

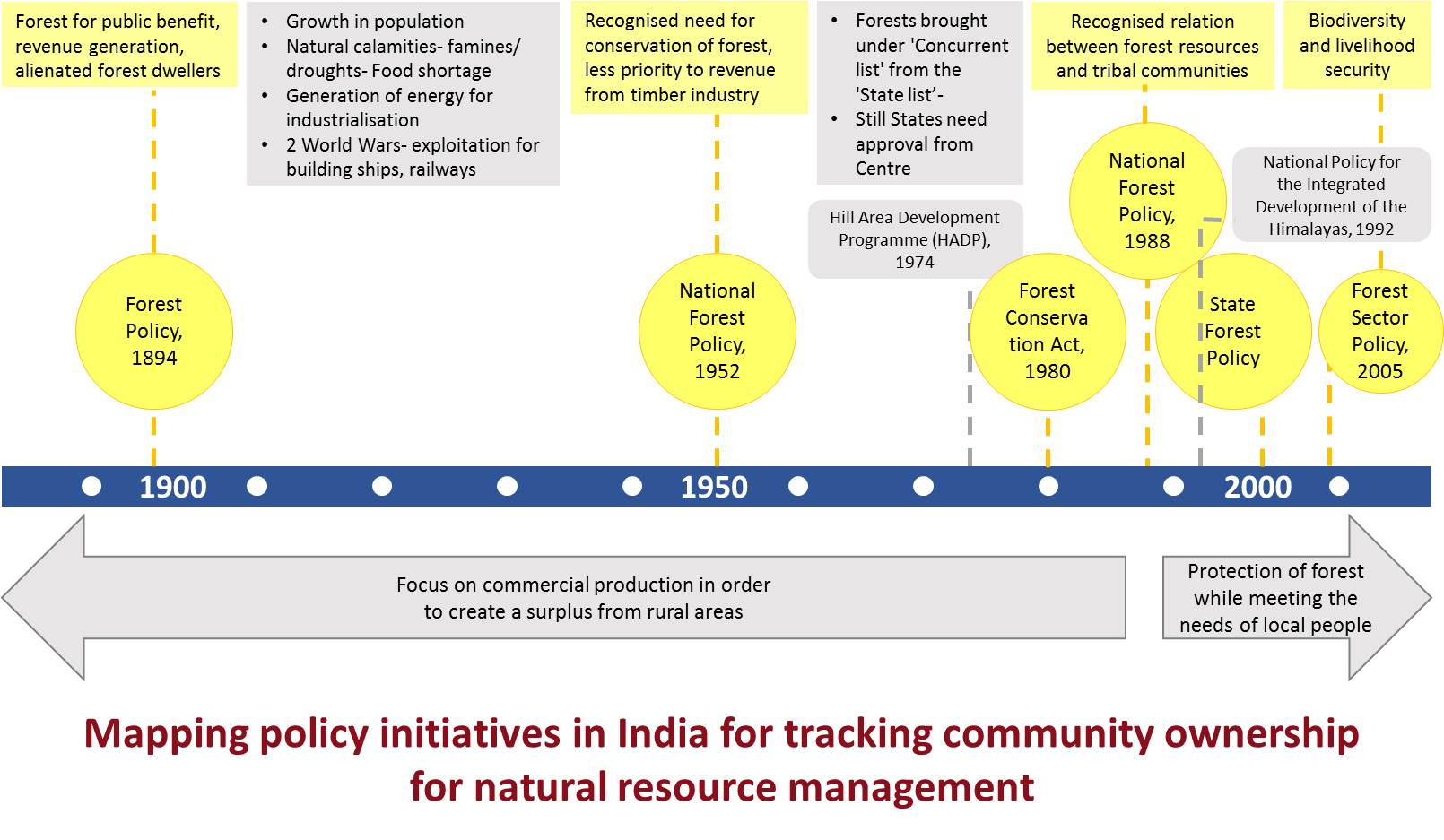

Policy Shift in Natural Resource Management over the years

The Himalayas have seen two distinct phases

in its timeline since the 20th century. The first was the incessant

clearing of forests for the growth of the timber industry. This was on

account of the quest for more revenue and the insatiable demand for

timber by the railways and military in the economy under the British

rule as shown in the figure. The State Forest Policy of 2001 did take into account the above-mentioned factors, but there has been ambiguity in its implementation as there has been a rise in imported building materials like cement, which means that there has been a significant drop in the use of vernacular materials like timber and stone. For example, a renowned cement company has increased its number of integrated cement plants in India from 12 to 18 (Global Cement, 2017). The new assets are in Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh. Two of the states mentioned fall under the ecologically-sensitive Indian Himalayan Region and thus face harsh impact. Within policies for the Himalayan region, there is also need for a specific regional analysis instead of assuming uniformity to the entire area. Problems of the 12 Himalayan States of the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) vary from state-to-state. There is also an urgent need to strengthen co-operation among stakeholders in the affected states for an integrated approach. Policy Initiatives in Mountain Ecosystems A Planning Commission Task Force has recommended that, “the balance between natural resource exploitation and conservation should tilt in favour of the latter” (Planning Commission & GBPIHED, 2010). The ground realities are however quite different. Natural and climate change induced disasters negatively affect tourism: The economy of most of the states in IHR has been largely dominated by the services sector. Tourism is a major driver of economic growth and livelihood promotion in many of the mountain states like Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim etc. In order to further boost investment in the tourism sector, the Government of Uttarakhand has given 'industry' status to the tourism sector. But disasters play a very important role in controlling influx of tourists in the state. For e.g. the number of tourists visiting Uttarakhand had increased from around 11 Million in 2000 to 28 Million in 2012. But in the year 2013, after the devastating floods and landslides in the state, there was a 30% decline in tourist visits. In 2014, the state regained its momentum and witnessed 10% growth in total tourist visits. The total tourist visits in Uttarakhand are expected to reach around 67 Million by 2026 (Uttarakhand Tourism Draft Policy, 2017). However, the increased probability of extreme events, climate change triggered disasters, would continue to haunt tourism's growth, development and sustainability in Uttarakhand. Compensation to states for their standing forests: The 12th and 13th Finance Commissions have included the concept of compensating states for standing forests in their reports. Unfortunately, the funds provided for these services are meagre and currently unavailable. The policies urgently need to evolve with regard to building the local economies and working with the rural populace in accordance with their resource demands from the forests. Unplanned development: The main reason for the floods having caused so much havoc in Uttarakhand was due to ill-planned or unplanned development, specifically in three areas – road construction, building construction and mining in the riverbeds. Insensitive construction: The foremost shortfall in the field of conservation of the mountain ecosystems is the incessant government grants for large construction projects like hydel power which are completely insensitive to the ecology and the communities. In Uttarakhand on the Ganga basin alone, the government has identified projects adding up to nearly 10,000 mw of power and plans for 70-odd projects (Narain, Himalayas: The Agenda for Development and Environment, 2013). Illegal mining: The materials to construct buildings – sand and gravel – are mined from the riverbeds and forest areas illegally. The state government's data shows that 1,608 hectares on the riverbeds were mined in 2012. The state's forest department says that between 2000 and 2010, almost 4,000 hectares of land previously under its jurisdiction was diverted for mining. The result is that when there is a flood, there is no check on the huge boulders rolling down the riverbeds and causing havoc along the banks. Material regulation: Vernacular building practices are developed with locally available, easily workable and natural building materials which are mostly renewable in nature (like timber, thatch, mud and bamboo), have good climatic response and have no adverse effect on the health of residents and little or negligible impact on the environment of hill settlements. Now, contemporary building materials are manufactured from raw materials, which are transported from different parts of the country after manufacturing. These materials have high embodied energy and cause a lot of pollution during manufacturing and transportation and are mostly inappropriate to the context of hill settlements. Earthquake resistant construction and safety regulations: Safety against natural hazards is the most serious concern for planning and design of buildings in hill regions. Many vernacular practices like dhajji wall, kath-kuni, koti-banal, taaq and wooden buildings have good response during previous earthquakes (Kumar and Pushplata, 2008). However, presently adopted construction practices in hilly areas do not have good earthquake response and may result in serious damage and loss of precious human life and resources. Need for Integrated Mountain Development Seeing the growing attraction of tourism industry in these mountain states, there is a need for creation of ecologically responsible tourism through Integrated Mountain Development. Ecotourism helps in community development by providing alternate, sustainable sources of livelihood to local communities. Its aim is to conserve resources, especially biological diversity and maintain sustainable use of resources while at the same time gain economic benefit. A recent project undertaken under the National Mission of Himalayan Studies by Development Alternatives in collaboration with Himalayan Environmental Studies and Conservation Organisation aims to fulfil the requirement of the livelihoods needs of the local youth and women to boost the local rural economy. This project is centered around conserving the natural ecology and biodiversity of the mountain region with the help community initiatives which will include sustainable local tourism-based livelihoods and tourism led responsible economic growth of the state. ■

Srijani Hazra

Mausam Jamwal

References: |