|

The Ganga Water Machine Ashok Khosla

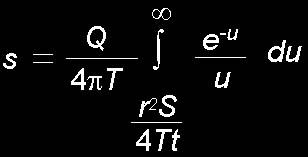

T he Ganga River Basin is one of the largest single bodies of fresh water in the world. In addition to the dozens of mighty rivers that flow into the Ganga, the sedimentary aquifers hold a vast sea of fresh water under the ground, spreading out from the banks along the length of these rivers. Within India, the Gangetic Basin covers more than 800,000 square kilometers, with the larger tributaries alone accounting for well over 10,000 kilometers of flowing water.Conjunctive use of ground and surface water, a technology well developed and tested elsewhere (particularly in California, Ohio and many other parts of the US), could bring about a major revolution in the management of our water resources in Northern India. In addition to creating the basis of vast new economic opportunities, including huge increases in food and energy production, improved flood and drought control, river transport year-round, better salt balance and port maintenance, it would provide ecosystem services of the highest value, transforming the lives and well-being of an entire nation. In a seminal paper entitled "The Ganges Water Machine", published nearly thirty years ago in the prestigious American journal Science (9 May 1975, Volume 188, pp 611-616 – reprints of which are available from the editor), Roger Revelle and V. Lakshminarayana showed how a carefully designed but simple method of creating underground storage of water along the rivers of the Ganga Basin could lead to dramatically better use of the region’s resources. This would produce massive increases in food production (by as much as a factor of three, they estimated at the time), more uniform flows of river waters throughout the year, lessening the possibilities of both floods and droughts, and the consequent improvements in downstream river quality. These, in turn, would lead to huge new opportunities for improving both the economy and ecology of the region. Here, in italics, are some excerpts from the original paper: The fundamental problems of land and water development in the Ganges Plain arise from the highly seasonal flow of the river and its tributaries. Nearly 84% of the rainfall occurs from June through September, and 80% of the annual river flow takes place during the 4 months of July through October. The dry-season flow of the Ganges is barely sufficient for the needs of India and Bangladesh. If irrigation with either groundwater of surface water continues to be developed along the lines of the present programs, the dry-season flow will be continually be reduced. …Because of the steep slopes of the Himalayan foothills and the flatness of the Ganges Plain, surface sites for storage are scarce, [and costly]. On the other hand, there are great possibilities for underground storage, which should be relatively inexpensive. There are at least five ways in which a portion of the monsoon flows coud be stored underground. Infiltration into the water table in the monsoon season could be increased by (i) water spreading in the Terai; (ii) constructing bunds at right angles to the flow lines in uncultivated fields to slow down run-off and increase infiltration; (iii) pumping out the underground aquifers during the dry season in the neighbourhood of nallahs which carry water during the monsoon; (iv) pumping out groundwater during the dry season along certain tributaries of the Ganges to provide space for groundwater storage [during the monsoon]; and (v) increasing seepage from irrigation canals during the monsoon season by extending the network of canals [,particularly leaky ones], distributaries and water courses for kharif irrigation and pumping this seepage water during the dry season. The method used to find the depression (or lowering) of the water table during low flow seasons is given below: The drawdown due to pumping in an acquifer is given by

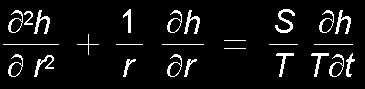

Where the drawdown s = h1 — h(m), h1 is the initial saturated thickness of the aquifer (m), h is the height of the water table during pumping (m), Q is discharge (m3/day), T is the coefficient of transmissibility (m2 / day), S is the storage coefficient (dimensionless), t is time since pumping started (days), and r is the distance from the pumping well (m). Equation 1 is the solution of the differential equation

subject to certain simple boundary conditions. Since Eq.2 is linear, the super-position principle can be used to find the solution when more than one well is being pumped in the aquifer. The advantages identified by the authors included: increased water available for irrigation during the rabi crop, reducing the huge seasonal variation in the flows of the tributaries and the main river, greatly reduced losses by evaporation, and all the consequent benefits for river transport, waste dilution, downstream uses, etc.

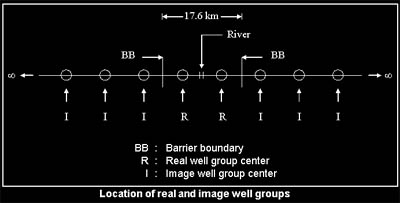

To work properly, the Ganga Water Machine must be designed properly. The authors provide the hydrological science that underlies this technology, which shows that the primary interventions required are the building of carefully spaced "well fields" on either side of the nallahs, canals and tributaries, and operating them so as to pump down the aquifers during the dry season and thus raising the surface stream flows considerably. During the monsoons, the five measures identified above to increase infiltration will refill the aquifers. Obviously, considerable energy is needed to run the Ganga Water Machine, but work by Development Alternatives has shown that only a small fraction of the irrigation water generated would be sufficient to grow the biomass needed to power the Machine. The revenues in terms of additional agricultural production alone would be much larger than the costs of all the energy required. Table depicting possible river reaches for underground storage of monsoon flows

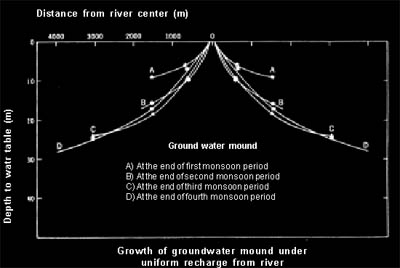

The accompanying equations and graphs give a glimpse into the mathematics underlying the working of the technology, showing that within a period of 3 or 4 years, a properly functioning Ganga Water Machine could establish a regime where the the ground water table would have been drawn down sufficiently to allow its conjunctive use with surface water to yield major improvements in the year round availability of these resources. The Table, taken from the original paper, gives an idea of the magnitude of the underground storage and lean season flow improvements possible for some of the tributaries of the Ganga – showing more than 10 Million hectare metres storage – comparable to the amount used for irrigation in the entire basin today. The beauty of the Ganga Water Machine, at a time when large-scale engineering works are so much in fashion, is that although it is based on a grand vision with potential region-wide impact, it can be implemented locally and piecemeal – an excellent example of a "glocal" intervention, where we can "Think Globally and Act Locally". This means that it allows for local participation, control and access to benefits, gradual investment of financial and engineering capital, low gestation periods and reduced possibility for frictional losses such as political patronage and corruption. And at the same time, it needs science and engineering of the highest sophistication. q |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||