|

Just Urbanisation City the Home for Prosperity1 We are being urbanified, more people live in cities than in rural areas. In the 1960s, 34% of the world lived in urban areas; today it’s 50% and by 2050 it will be 66% - indicating a 1.3 million people per week growth for urban areas.2 55% of the global GDP comes from cities (above 0.5 million), a share projected to increase to 60% by 2030 – implying that 64% of the GDP growth between 2012 and 2030 will come from cities.3 India itself has seen a rise in the urban population to 33%. Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata figure in the list of the 10 largest cities in the world with Ghaziabad, Surat and Faridabad in the 10 fastest growing cities. As per McKinsey4, urban India contributes to nearly 70% of the total GDP, 90% of the tax revenues and majority of the jobs. Rightly, the new sustainable development goals (SDGs) have created an urban specific goal focusing on cities and human settlements i.e. Goal 11 –‘Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’. This is not to say that rural areas are not important. Urban and rural areas are inextricably linked - one cannot function without the other. Such an interdependent system creates mutually reinforcing welfare impacts through increased access to markets, better infrastructure, higher remittances, healthcare and increased resilience to disasters. This has been recognised by the target 11.a ‘Support positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning’. Cities are the locus of opportunities such as innovation, jobs, creativity and economic growth. Cities are ‘change-makers' 5, however only if managed well. Unplanned and uncontrolled urbanisation creates heavy stresses and fractures in our social, environmental and consequently economic systems. The resultant urban sprawl and congestion leads to an inadequacy in the supply of basic services such as water, electricity, sanitation, transport, health, education and shelter. Furthermore, there are challenges of unequal access with women, children, urban poor and marginal groups being further deprived and marginalised. So while urban areas may be regarded as centres of growth and income, hard questions around their economic, social, ecological and institutional capacity (often very limited) need coherent answers and strong responses.

City Systems for

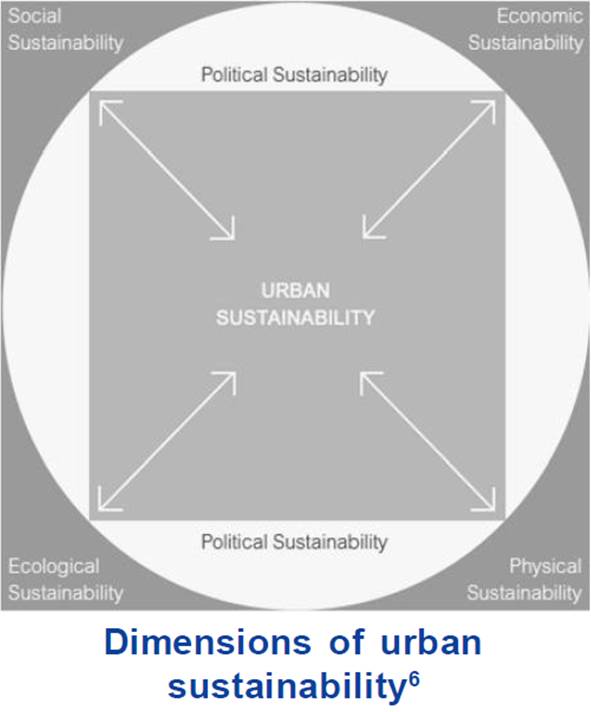

Sustainability There are 5 dimensions of urban sustainability – economic, social, ecological, physical and political (refer to diagram). In any urban area, as seen in the diagram, the outer circle symbolises its ecological capacity. This circle is a barometer of sustainability for the five dimensions - are the changes taking place for or against sustainability. As per Allen, the four corners of the square represent the economic, social, ecological and built environment dimensions, with the political dimension articulating them. In this sense, cities can be thought of ‘as systems of systems’ 7, making sustainable urbanisation complex, demanding integrated responses to the challenges and risks cities face. The political dimension is the mechanism that is used to synergise the other four dimensions of economics, social, ecology and physical. It is the cohesive force which ensures that the other dimensions remain within the boundaries of sustainability. Hence, it would be safe to say that without the political dimension or more commonly known as effective governance (political, institutional or administrative structures); sustainable development will not be possible. This brings our focus to Goal 16 in the new development agenda - ‘promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’. Sustainable urbanisation, in particular, requires a committed local government and participatory local democracy model. This fifth dimension includes all the relations of all actors at all levels. Such a multi-level governance or networked governance8 acknowledges the need to look beyond official urban boundaries and identifies these linkages. The Indian Urban Challenge Often unplanned and unanticipated, Indian urban growth has been as a result of private actions as opposed to a government strategy unlike the urbanisation trends in China primarily driven by local governments.9 Urban crisis in India is the result of years of poor and inefficient governance especially at the local level with a distinct practise to policy gap in the framework. As Chakrabarti10 notes, there is an urban laissez-faire – when cheap populist measures, excessive state control and bureaucratic intrusion, subsides and concessions were chosen over citizen engagement, sound financial considerations, capacity development of local bodies etc. There is a tendency to create new big projects, missions or programmes instead of ‘revisiting existing structures, reengineering the existing processes’11 or creating ‘a reform in the reform process’ 12. For example, the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) launched in 2002 looked more into remedial measures rather than the future of urban sustainability.13 In effect, the Indian urban governance framework adopted a reactive rather than a proactive approach almost making it seem as if India was a ‘reluctant’14 urbaniser. Some suppose that this is due to an accumulation of years of belief that urban was ‘evil’ or ‘India is country of villages’.15 This is reflected in the form of the massive gap in the provision of urban services wherein the demand usually exceeds the supply. For example, 54% of urban households do not have access to toilets, 64% are not connected to the public sewerage system and nearly 50% of the solid waste remains uncollected.16 The problem manifests from a complex institutional structure creating overlapping responsibilities and jurisdictions amongst the national, state and local governments. The result is ambiguity in the form of who is accountable and who plays what role. The problem is further compounded by poor autonomy of local governments. If we consider the political dimension of urban sustainability as the regulating mechanism, then there is a major gap within the Indian municipal cadre between capability and capacity to deal with the current and emerging challenges of urbanisation. This gap is manifested in terms of lack of financial as well as technical resources. The 11th Five Year Plan identified the lack of skilled manpower in Urban Local bodies as one of the key concerns. We cannot expect a ‘truncated urban government’17 to create the necessary transformations needed to create sustainable cities. While the political dimension must integrate, synergise and regulate the other 4 dimensions, some basic questions need to be answered - Who owns the city? What are the rights of urban dwellers? Who needs to lead the transformations? Who is accountable and for what? Also, the urban governance framework needs to create an integrated, systemic and proactive approach towards urban development and implementing the SDG agenda. With the launch of new big programmes such as Smart Cities or the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), the following questions call for some urgent responses: • What are the different city-types and thereby what are the differences in the challenges they face? This is especially important for India as the ‘impetus to urbanisation’ comes from an emergence of new urban centres as well as an expansion in municipal limits and urban agglomerates.18 • How do we create city-level indicators and collect data? If cities are different and their (citizen) needs are different, there is a need for indices to account for this differential. The next step therefore becomes establishing data systems both in terms of collection and analysis to measure and monitor the progress against the SDGs in a meaningful way. • How do we finance the systemic risks and challenges faced by cities, when donors characteristically adopt a sectoral-based funding approach?19 • How do you create a more participatory and autonomous form of local democracy? In particular to look at 74th Amendment Act, which devolves powers to city level governments but clearly there is disconnect between policy and its implementation. • How do you involve the citizenry in local decision-making? What will be the relationship between local city managers and citizenry and how will this be shaped? Will different cities need a different approach? The urban revolution is definitely underway. The fate of India’s current 350 million strong and future 600 million (2031) urban dwellers depends on a strong, responsive and resilient urban governance framework. q Mandira Singh Thakur Endnotes 1 UN-HABITAT 2 Floater, G. and Rode, P.,2014, Cities and the New Climate Economy, LSE Cities, Paper 1 3 ibid 4 McKinsey, 2010, India’s Urban Awakening, McKinsey Institute 5 UNDP, 2012, One Planet to Share, Asia-Pacific Human Development Report 6 Allen A., 2009, Sustainable Cities or Sustainable Urbanisation?, UCL Journal Summer Edition 7 Cardama, M., 2015, Inextricably interlinked: Urban SDG and the New Development Agenda, Citiscope 8 Rode, P. and Shankar P., Governing Cities, Steering the Futures, Governing Urban Futures 9 Floater, G. and Rode, P.,2014, Cities and the New Climate Economy, LSE Cities, Paper 1 10 Chakrabarti, P.G.D., Urban Crisis in India, UNRISD 11 Gopal, K., 2012, Sustainable Cities for India- Can the Goal be Achieved?, FUTURARC 12 Chakrabarti, P.G.D., Urban Crisis in India, UNRISD 13 Gopal K., 2012 14 Tiwari, P. et al, 2015, India’s Reluctant Urbanisation, Palgrave Macmillan 15 ibid; Sanyal et al, n.d.,The Alternative Urban Futures Report, WWF 16 Jain, A.K, 2011, Sustainable urban planning, Architecture - Time, Space and People. 17 Gopal, K., 2012 18 Kundu. A , 2013 , Exclusionary cities: The Exodus that Wasn’t, Infochange Agenda 19 Sung Courtney, 2015, Know Your SDGs: Solutions for an Urban Century, Chemonics

|