|

What is 'Sustainable' about

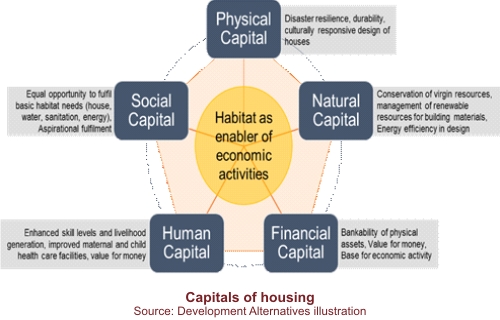

Sustainable Housing? Defining Sustainability in Housing Defining Sustainability in Housing When it comes to using the term 'sustainability' in housing, it is often misinterpreted as sustainability of a building, usually confined to physical features like rain-water harvesting, waste management, energy efficient lightning etc. While at first glance one may not see the difference, however delving more into defining 'housing', it ideally refers to social, cultural, economic, financial and environmental sustainability. Similarly, terms like sustainable cities, sustainable transport, sustainable energy etc. are loosely used, without giving proper thought to what 'sustainable' means. Virtually everyone is familiar with the Brundtland Commission's definition of sustainability, which defines sustainable development as 'meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.' The concept of sustainable development was initially conceived as a term most relevant to macro-economic development . However, it is only more recently that it has been applied to a consideration of the quality of development in human settlements and, thus by implication, housing.

Choguill (2007), in attempting to define

sustainability in housing, states that 'if the concept of sustainability

of human settlements is to have any meaning at all, it must be defined

to include staying within the absorptive capacity of local and global

waste absorption limits, the achievement

of the sustainable use of renewable and replenishable resources, the

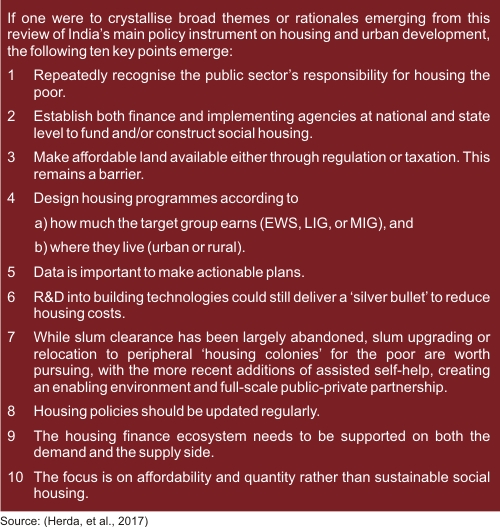

minimisation in the use of non-rene Thus, one is of the opinion that in order to be sustainable, housing initiatives must be economically viable, socially acceptable, technically feasible and environmentally compatible. Government housing policy must obviously be directed to achieving these desirable aims. Housing Policies in India Given the extent of the housing challenge in India, India has had a history of numerous policies and missions focusing on housing which range from target schemes for low income groups (Low Income Group Housing Scheme, 1954), the Urban Land (Ceiling Regulation) Act 1976 which was enforced to prevent land speculation and to ensure optimal allocation of land and the National Housing and Habitat Policy, 1998 which focussed on fiscal concessions, legal and regulatory reforms and emphasised on the creation of strong PPPs to resolve the housing problems. In the recent years, the focus has been on increasing and strengthening the housing stock of vulnerable communities of economically weaker sections (EWS) and LIG with greater financial assistance in the construction of these houses. While many of these 'rationales' can and should be questioned, the last point especially is quintessential to the concept of sustainability, for which it is argued that both housing and resource-efficiency objectives under both national and international agendas should be pursued concurrently.

State Housing Policies and Sustainability Under the Constitution of India, housing is a state subject and comes under the purview of the state government. So far as the state housing policies go, each state has various schemes and regulatory reforms attempted to influence the construction of EWS/LIG housing. Development Alternatives, under the project funded by UNEP under its 10 YFP programme on Sustainable Buildings and Construction, 'Mainstreaming Sustainable Social Housing in India' (MaS-SHIP) undertook a small study to assess state housing policies and their commitments to affordable and sustainable housing. One state in each climatic zone was selected, namely, Rajasthan (hot and dry), Andhra Pradesh (warm and humid), Uttar Pradesh (composite), Karnataka (temperate) and Uttarakhand (cold). In the case of the state of Rajasthan, in order to incentivise private developers, the state government has stated that private developers constructing 100% EWS/LIG housing on their own land, will be incentivised by either Land Use Conversion Fee Waivers or a Floor Area Ration (FAR) of up to 2.25 will be given. Further under the Mukhyamantri Jan Awas Yojana 2015, the goal of which is to ensure 'affordable housing for all and integrated habitat development in general and for EWS/LIG in particular,' the state has taken initiatives to encourage use of alternate building construction materials (in this case fly-ash bricks) and the installation of rainwater harvesting systems. In Uttar Pradesh, the affordable housing policy allows for a maximum FAR of 2.5 and density of 450 housing units per hectare. If incentives are to be provided by the state, the housing project must have a GRIHA certification and the state government will allow 5% extra FAR for green development projects exceeding 5,000m2. It is one thing for state governments to incentivise developers to construct affordable housing projects, however it is another thing for such projects to materialise on the ground and be successful. At this juncture of India's development, there seems to be a misinterpretation thus leading to incorrect conceptualisation of 'housing' and 'sustainability'. There is a significant divergence between specific development policies. The National Mission on Sustainable Habitat, 2010, one of the missions under the National Plan on Climate Change, sees no mention in any of the state housing policies or vice-versa. Although there is increasing knowledge on sustainable development globally and in recent years, nationally, one critical dimension of urban housing problems is that sustainable housing is yet to gain its widely acknowledged importance in a country like India. This is due to the lack of understanding of the social, economic, cultural and environmental components of sustainability in housing development. Thus, it is important that India's housing policies start to recognise that 'affordable housing for all,' should mean sustainable housing, i.e. meeting the basic needs of the present generations in a sustainable manner, so as to not compromise the future generations to meet their basic needs. ■ References: Choguill, C. (1999). Sustainable human settlements: Some second thoughts. Sustainable cities in the 21st century , 131-142. Foy, G., & Daly, H. (1992). Allocation, distribution and scale as determinants of environmental degradation: Case studies of Haiti, El Salvador and Costa Rica. Environmental Economics, pg 298. Hardoy, E., Miltin, D., & Satterthwaite, D. (1992). Environmental problems in third world cities. Herda, G., Caleb, P., Gupta, R., Behal, M., Gregg, M., & Hazra, S. (2017). Sustainable social housing in India: definition, challenges and opportunities- Technical Report. Oxford Brookes University. IUCN. (1980). World conservation strategy: Living resource conservation for sustainable development. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; UNEP; WWF. Rees, W. (1996). Revisiting carrying capacity: Area-based indicators of sustainability. Population and Environment, 17(3). Sarafy, S. E. (1989). The propoer calculation of income from depletable natural resources . Environmental accounting for sustainable development.

Pratibha Caleb

|

wable

resources, and meeting basic human needs. It is the last component,

concerning human needs, that distinguishes this definition from the more

general environmental approach to sustainability that provides the

value-add to the concept of sustainability. It is the two, i.e., meeting

basic human needs and environmental sustainability that function within

a circle, both equally dependent on each other to ensure 'sustainability

of human settlements'.

wable

resources, and meeting basic human needs. It is the last component,

concerning human needs, that distinguishes this definition from the more

general environmental approach to sustainability that provides the

value-add to the concept of sustainability. It is the two, i.e., meeting

basic human needs and environmental sustainability that function within

a circle, both equally dependent on each other to ensure 'sustainability

of human settlements'.