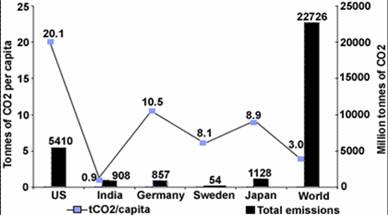

| Tackling Climate Change: Our Collective Way Forward V ast stretches of dead, barren farms, covered with dried-up, stunted cotton and other crops lie abandoned even as jobless farmers and labourers gather at village chaupals, doing nothing. Reason, they have done their best. Some have sowed thrice; some did it even four times and have stretched their capacities beyond limit. But with produce dwindling from tonnes to kilos, they have turned into paupers, too numb to respond to the calamity.This is the situation in Vidarbha and Marathawada regions of Maharashtra, India where drought is becoming a perennial and recurring feature. Nearly 10,000 villages are severely affected. Almost 10 million people’s basic systems of livelihood are shattered and they are desperately fighting odds to survive. Climate change is already hitting people’s lives and hard.The scenario is not going to be any brighter in the near future. The latest reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predict that climate change will soon bring an additional 49 million people in Asia into the folds of hunger and malnutrition, leave 94 million people at the mercy of coastal floods and put 50% of Asia’s total biodiversity at risk (See inset). When one looks at the predictions for the poor nations of Africa and Latin America, the picture looks even more alarming. It is certainly time that climate change is taken very very seriously. The concerns expressed over climate issues by NGOs and governments are already beginning to show up in policy and business decisions. Aside from the Kyoto Treaty—which the US and Australia, two of the biggest polluters, have not signed—individual governments at the supranational, national, regional, and state levels are coming up with their own regulations on carbon emissions, the prime cause of climate change. The European Union’s Emission Trading Scheme came into force in January 2005, and state and regional governments in Australia, Canada, Japan, the United States and elsewhere have also set up new rules. The climate change phenomenon has also made businesses feel the heat. Between 1980 and 2004, the payouts by the Insurance industry due to weather-related losses have quadrupled. Large institutional investors such as Calpers and the pension funds of New York State are pushing companies to report their carbon ‘footprint’—the total amount of carbon dioxide that they and their suppliers emit—and to define their risk exposure to regulations that limit emissions. As per a McKinsey Report, ‘This intensifying level of scrutiny isn’t simply a call for environmental stewardship. Rather, it is born of concern that over the next 5-15 years, the way a company manages its carbon exposure could create or destroy its shareholder value. The companies with the most to lose, at least initially, are those whose production processes generate a lot of greenhouse gases.’ Rising input costs—for energy or transportation—will affect companies of every stripe, including manufacturers, retailers, banking firms, airlines and almost every other type. The investors will increasingly hold them responsible for managing emissions. They might also find their share prices discounted in capital markets. Contrastingly, companies that have begun making smart investments in their emission reductions are already reaping the benefits. For instance, British Petroleum saved money in its emission reduction programme within its plants. Witness John Brown, Chief executive of BP, who writes: ‘Counter intuitively, BP found that it was able to reach its initial target of reducing emissions by 10% below its 1990 levels at no extra cost. Indeed, the company added around $650 million of shareholder value, because the bulk of the reductions came from the elimination of leaks and waste.’ The Global Climate Policy Climate being a global public good, the strategy to deal with it also has to be global. This understanding formed the basis of establishment of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1990. Under the auspices of the UNFCCC, two broad sets of activities to tackle the climate problem have emerged. They are climate change mitigation (prevention of climate change through GHG emission reductions) and adaptation (adjustment to climatic changes). Climate Change Mitigation International efforts to curb greenhouse gases have culminated in a legally binding treaty, famously known as the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. The Protocol is based on the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ of all nations to take measures to stabilize GHG emissions in the atmosphere. It requires 35 industrialized countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to about 95% of their 1990 levels in the first commitment period (2008-12). In spite of being legally binding, the Protocol has not turned out to be as effective as it was intended to be. ‘From 2000 to 2005, the growth rate of carbon dioxide emissions was more than 2.5% per year, whereas in the 1990s it was less than 1% per year,’ noted Dr Mike Raupach, of the Australian government’s research organization CSIRO, who co-chairs the Global Carbon Project. As precedents, however, the UNFCCC and Kyoto Protocol have been significant in providing a means to solve a long-term international environmental problem. The Kyoto Protocol’s most notable achievements are the stimulation of an array of national policies and the creation of a functioning market for GHG reductions. For this global mechanism to be more effective, the first commitment period needs to be followed up by measures to achieve deeper reductions (at least 60% from the 1990 levels) and the implementation of policy instruments covering a higher share of global emissions. Adaptation to Climate Change Another issue of significance in the climate arena is that of adaptation to climate change. In simple terms, adaptation is the ability to make adjustments to infrastructure, livelihoods and production systems in order to minimize the negative impacts of climate change and benefit from any opportunities. The issue of adaptation has increasingly become important since the developing nations started facing loss of lives and livelihoods due to climate-induced events. Nordhaus, whose work in this arena spans 3 decades, estimates that for a +2.5 oC warming, one might expect to see global damage amounting to 1.5-1.9% of world GNP. However, in Africa, that impact might be closer to 4% and in India, 5%. The more politically moderated Third Assessment Report of the IPCC reported that while developing countries are expected to experience larger losses, global mean losses could be 1-5% GDP for 4° C of warming. The recently released Fourth Assessment Report (FAR) of the IPCC notes that ‘there are some impacts for which adaptation is the only available and appropriate response’.Issues in the Global Climate Policy The policy makers have late been grappling with several issues as regards the climate policy. Decisions on many of these issues could fundamentally affect the lives of billions of people across the globe. We take a look here at some of these issues: Balance between Mitigation and Adaptation Science has now provided us with compelling evidence that climate change is happening and some of its adverse effects cannot be avoided even if all the GHG emissions are stopped from now onwards. The issue, therefore, is no longer mitigation versus adaptation, but it is of how much mitigation and how much adaptation. The issue between mitigation and adaptation is clearly one of balance. Most adaptation expenditures would be local, while mitigation requires action on a global scale. However, certain impacts in the near future necessitate that adaptation is supported within the developing countries on a large scale. Although adaptation has so far played a second fiddle to mitigation issues, developing countries have now joined forces to bring it out much more explicitly within the negotiations framework. Balance Between Mitigation Now or in the Future The global policy decisions also largely depend on the differential welfare impacts of the quantum of mitigation efforts undertaken now or in the future. Economist Nicholas Stern, in his famous report submitted to the British Government says, ‘For every £1 invested now we can save £5, or possibly more, by acting now.’ On the contrary, Nordhaus has argued the exact opposite, suggesting that little should be done to reduce carbon emissions in the near future. The idea behind this is to invest in physical and human capital now so that the future generations, with more resources and efficient technologies at their disposal, can tackle the climate threat more cost effectively than the present one. Choosing any one of the options is not purely a matter of balancing costs and benefits but also a question of how to distribute the benefits of energy consumption, land use and favourable climate among generations. Action aimed at preventing climate change today would place a burden on people now alive and would probably leave the coming generations with a climate more similar to today’s—but with somewhat less wealth—than they would have had otherwise. In contrast, not acting would benefit people today and probably yield somewhat more wealth in the future—but it might also leave the world with a different and possibly worse climate for many generations to come. The next 3 years before the expiry of the first commitment period will see detailed negotiations on the reduction commitments by the world’s major emitters. There is now an urgency to reach this agreement as soon as possible to give countries time to ratify as well as prevent the collapse of the carbon market, which is now creating a price signal for GHG reductions. Who Should Undertake Mitigation? If an average American or European citizen lived like an average Indian or Chinese, we would not be worried about the climate problem. Only 25% of the global population lives in developed countries, but they emit more than 70% of the global CO 2 emissions (Parikh et al., 1991). In per capita terms, the disparities are also large: an Indian citizen emits less than 0.88 tonnes of carbon per year, whereas a citizen of the USA, for example, emits more than 20 tonnes.It is this inequity among nations that is the core of the intense discussions on ‘who should reduce and by how much’. The reason for this is that it is not just an environmental issue. In fact, the Chancellor of the Exchequer of the U.K declared that ‘climate change is an issue for finance and economic ministries as much as for energy and environmental ones’. The reason for this is purely economic. More and more countries will need increasing amounts of energy. Since 1986, the world’s demand for energy has been growing at a rate of 1.7% a year. With the rapid growth of the BRIC (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) economies, this demand is expected to grow at the rate of 2.2% per year. The new energy scenarios will be characterized by: · Shifting production bases of basic material (such as steel, copper) from developed to developing countries, especially in Asia. (China, by 2015, will have 30% of world’s steel-making capacity; Dubai is a already a leading producer of aluminium).· Falling share of industry (as a result of a shift towards less energy intensive service industries) and increasing share of consumers as users of energy in developed countries. Sectors catering for consumer goods account for 53% of global energy demand, while the residential sectors account for 25% of the global demand.· Growing competition over access to energy sources, particularly among countries and regions (China, India, Europe, and the United States) that consume more energy than they produce. The likes of EU – Russia Energy Alliance and the Indo-US Nuclear deal already reflect the growing urgency.The situation in the next 20-25 years will, therefore, be characterized by a complex mix of factors. Developing countries will need more and more energy to develop their economies and eliminate poverty; they will also be catering to industrial and consumer needs of the developed countries and, therefore, will contribute proportionately much more to the growth in the world’s carbon emissions. However, on a per capita basis, the developed countries’ emissions would still be 2-3 times higher than even India or China, two of the biggest emitters amongst the developing countries. The question, therefore, of who should mitigate, is ethical. Developed countries (the US, Japan, and European nations) argue that fast developing countries like India, China are also significant contributors and should, therefore, also commit themselves to reduce emissions. In contrast, the developing countries emphasize that developed countries are responsible for the bulk of historical emissions and that these countries should shoulder any near-term burden of reducing emissions. This is well reflected in the demand by the Chinese representative in the UN General Assembly’s thematic debate on Climate Change, ‘The luxury emissions of rich countries should be restricted, while the emissions of subsistence and development emissions of poor countries be accommodated’. How to Share Adaptation Costs? Taking into account only the costs required to ‘climate-proof’ investments (ODA, foreign direct investments, and domestic investment), the World Bank recently estimated that the annual adaptation costs in developing countries could range between US $ 10 billion and $ 40 billion. It is now generally accepted that industrialized countries bear a certain responsibility for adaptation to climate change in developing countries, and should bear part of the costs. It is also in their self-interest to do so. A lack of sufficient adaptation in developing countries is likely to affect industrialized countries, for example, through a decrease in world trade, increased spread of diseases and increased migration flows. Most importantly, however, is the risk that there will be no global or near-global climate regime without an effective global framework for addressing adaptation, since increased support for adaptation is a declared condition for developing country participation in any future regime. In the present framework, most of the funding available for adaptation activities is the result of a pledge from the EU and other industrialized countries made in 2001 when developing country support was key to ‘Keep Kyoto Alive’. The resources committed through this pledge are channeled through three funds under the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol: the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), and the Adaptation Fund. Once again, the primary debate on the issue of sharing adaptation costs arises from the counter arguments of the developed and the developing countries. The developing countries feel that the contributions by developed countries to adaptation funding to date have been voluntary, not directly tied to any particular underlying rationale, metric of obligation, or indicator of need and have, thus, been small in relation to the scale of the challenge. They should, therefore, accept legally binding commitments on adaptation as well, akin to mitigation targets. The developed countries argue that there is a risk that adaptation becomes an endless demand for funds for projects with little understanding of the effectiveness of these funds at reducing the impacts of climate change since monitoring and measuring the effectiveness of adaptation initiatives could prove to be very challenging. Conclusion With climate change becoming more certain and the signs of climate change becoming increasingly evident, the issue is certainly on top of every policy makers’ agenda. The global efforts,maker's under the auspices of the UNFCCC, have so far yielded positive results, in terms of both the advancement in knowledge as well as creating global mechanisms, like the carbon market. The global climate policy framework is, however, increasingly getting mired in ethical and political issues, as outlined above. All eyes will now be on Bali, Indonesia, where the discussions on the future of the fight against climate change will be held on December 2007. Besides ongoing efforts, it may be time for us to look at other similar processes (e.g., the WTO) and learn from them. One such lesson may be to also look at bilateral or regional arrangements, outside of the UNFCCC process. The G8 nations’ engagement of the 5 major countries is one such step. The Asia Pacific Partnership for Clean Development and Climate, with the participation of the US, India, China, Japan, Australia and New Zealand is another example. As regards adaptation, it needs to be given much more emphasis and space within the negotiations and innovative methods for financing it, such as legally binding commitments on adaptation, internalizing adaptation into the existing bilateral and multilateral Overseas Development Assistance, putting a levy on JI (Joint Implementation) projects similar to CDM projects, etc., may be analytically explored further. All in all, the scientific and economic reports have told us that climate change is not an insurmountable problem and a bulk of it can be tackled with the technologies and resources available now. The 10 million people in Vidarbha and Marathawada and billions in other parts of the world deserve it to be done quickly. qUdit Mathur umathur@devalt.org |

A very convenient way of ascertaining this is to compute the ‘social cost of carbon’ (SCC), i.e., the money value of the damage done to the world as a whole from one extra tonne of carbon released now. The FAR provides an average SCC value of US $ 43 per tonne of carbon for the year 2005. To make correct judgments, however, the concept of SCC also needs to incorporate the damage in reduction due to adaptation measures. The optimum balance between mitigation and adaptation is to be achieved by comparing the SCC (including adaptation) with the cost of controlling an extra tonne of carbon emission (marginal cost of control). If the SCC exceeds the marginal costs of control, then, prima facie, greater focus has to be on more mitigation and vice versa.

A very convenient way of ascertaining this is to compute the ‘social cost of carbon’ (SCC), i.e., the money value of the damage done to the world as a whole from one extra tonne of carbon released now. The FAR provides an average SCC value of US $ 43 per tonne of carbon for the year 2005. To make correct judgments, however, the concept of SCC also needs to incorporate the damage in reduction due to adaptation measures. The optimum balance between mitigation and adaptation is to be achieved by comparing the SCC (including adaptation) with the cost of controlling an extra tonne of carbon emission (marginal cost of control). If the SCC exceeds the marginal costs of control, then, prima facie, greater focus has to be on more mitigation and vice versa.